Inside the Markets Aggregating Political Reality

“All voting is a sort of gaming…and betting naturally accompanies it”

–Henry David Thoreau, 1848

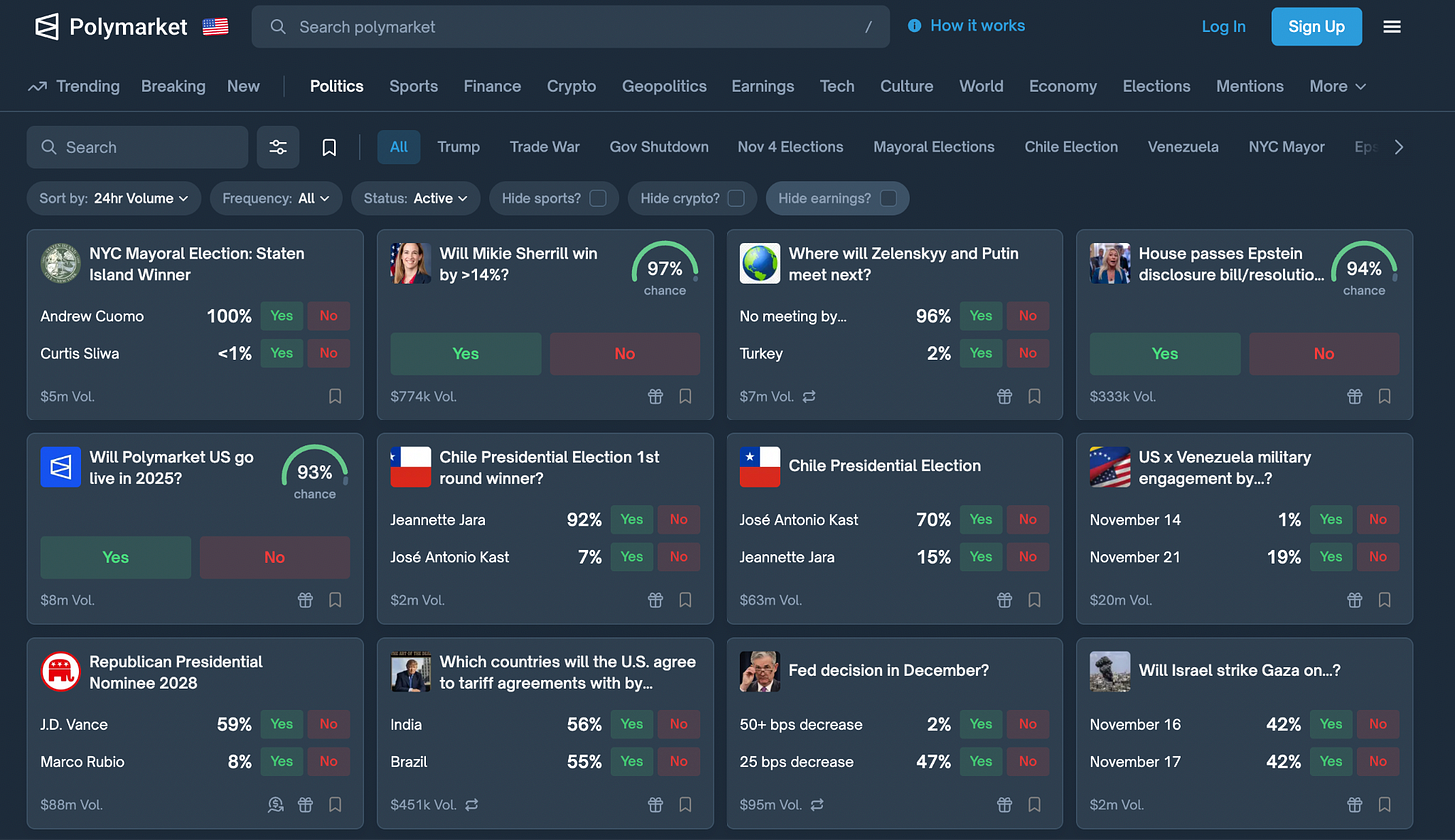

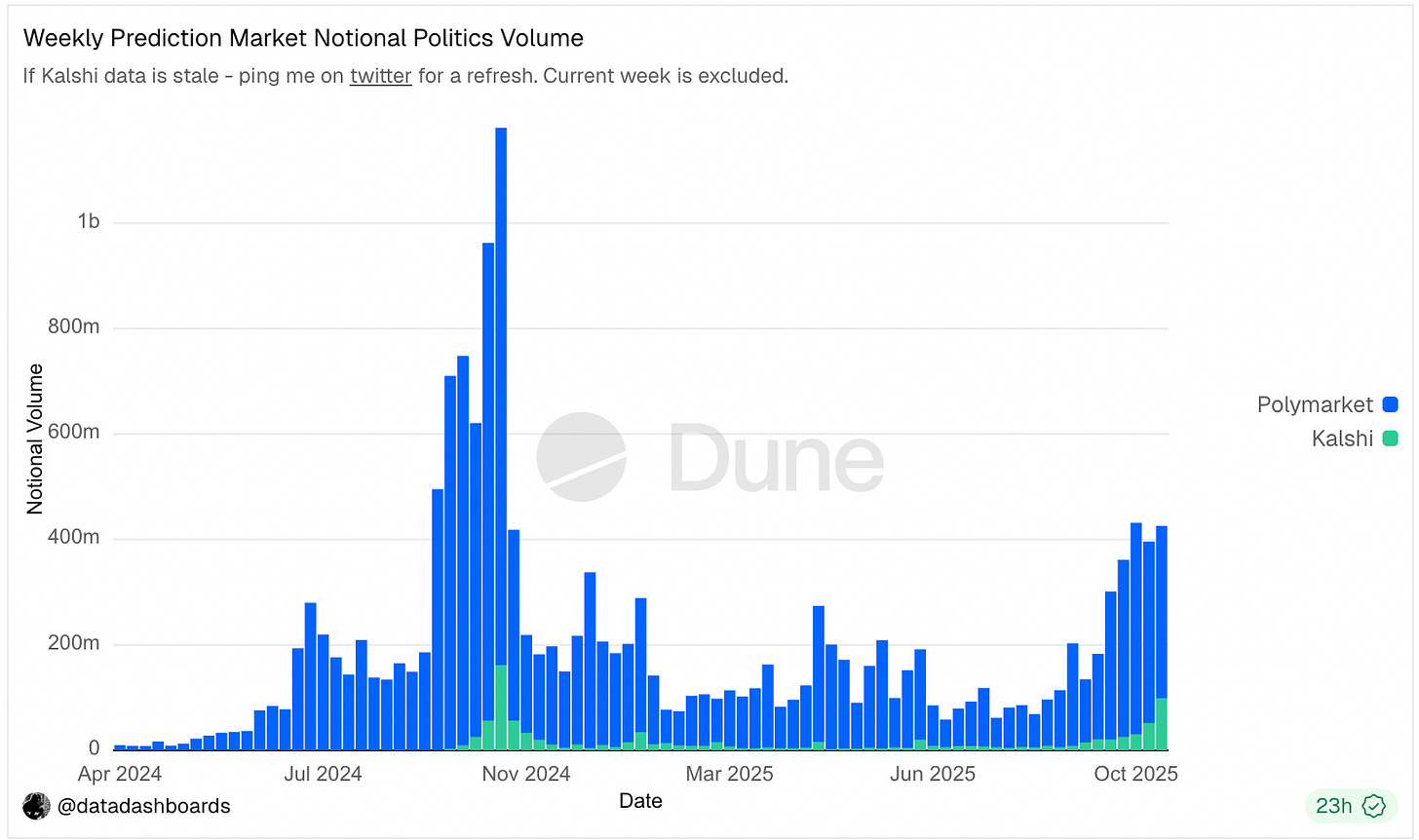

New technologies keep rewriting the rules of political life, from the internet to social media and AI. Now, hyperscaled prediction markets like Kalshi and Polymarket, which saw their combined trading volume exceed 7 billion dollars last month, are changing how we monitor and understand politics.

I’ve studied political prediction markets for years, and their early history is full of clever designs and unrealized promise. But what’s happening now is fundamentally different. The scale, the liquidity, and the attention these markets are attracting represent a break from efforts of the past.

My broader project is to understand how we preserve liberty in an increasingly algorithmic world. Prediction markets are a fascinating case where individuals, freely pursuing their own incentives and acting on their own information, can generate a public good for the digital era: a clearer shared picture of a highly complex political environment. At the same time, they can also create strange feedback loops that require careful governance. So they’re well worth studying.

To learn more, I decided to see them up close. Two weeks ago, I flew to New York City for election night and joined a group of academics, technologists, and prediction-market traders to run a real-time experiment betting on actual elections.

Over the course of the night, I witnessed a technology that has incredible potential to make us smarter and more informed about politics and the world——and which raises profound questions about what politics looks like in a world of live probability feeds where truth is often contested and frictionless information overwhelms our narrow attention spans.

Prediction markets are part of political discourse now

Prediction markets are becoming deeply ingrained in our discourse. The media——and Google——is reporting constantly on the ebb and flow of prediction market prices. Zohran Mamdani referenced Kalshi publicly. South Park did an entire episode on them. These markets are both contributing to our information environment, and also being influenced by it.

Election night is extremely frenetic on prediction markets, as I experienced firsthand in New York. After a day of waiting around for polls to close, there are sudden bursts of activity as vote counts start to trickle in. With each dump of new election data, we didn’t just analyze their meaning statistically——we also monitored posts from election experts, new sources, pollsters, and traders on X. The markets rapidly distilled data and social media hot-takes into cold, hard prices that moved rapidly in response to both the latest official information and the latest ‘vibes.’

This makes sense, because prediction markets for politics are exploding right now. During the 2024 election, Kalshi and Polymarket saw more than $1b in volume. The Nov 2025 elections——obscure, off-cycle elections that normally receive very little attention from Americans——saw more than $400m in volume during the final week. These numbers are sure to be larger in 2026 and beyond.

A long research tradition shows the value of political prediction markets

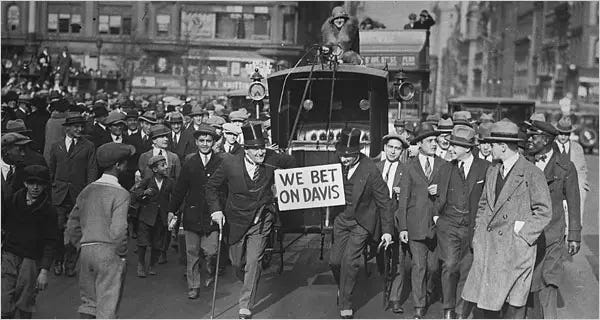

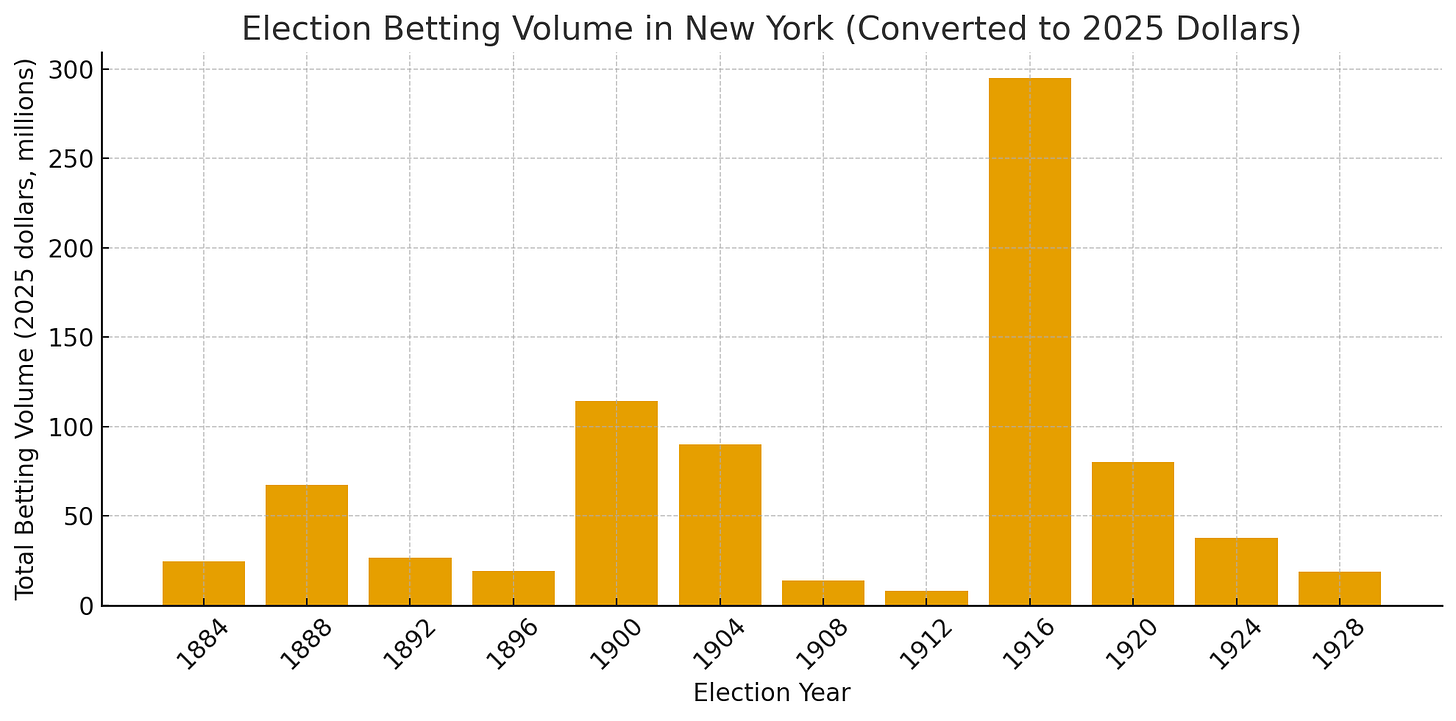

The scale of today’s political prediction markets is new, but prediction markets and betting markets for elections are surprisingly old. In a fascinating study, Rhode and Strumpf showed just how extensive the political betting markets of the late 19th and early 20th century were. As the graph from their data shows, betting volumes were generally high, exceeding $50m a number of times and peaking at nearly $300 million (in 2025 dollars) during the 1916 election.

Rhode and Strumpf show that these early betting markets were remarkably good at predicting the winners of elections, though they tailed off in efficacy and popularity once polling was invented, as Erikson and Wleizen showed.

By the 2000s, electoral prediction markets were once more a thing. Research again showed these markets predicted outcomes well, and academics explored a range of interesting ideas that these markets could unlock——such as inferring how different primary candidates were expected to perform in the general election or using them to make better collective decisions, as Robin Hanson has made famous. But these ideas were ultimately limited by the pitifully small volumes in these prediction markets.

Kalshi and Polymarket have changed the game, finally delivering the kinds of volume and liquidity that researchers have dreamed about. Even if they may not always outperform polls, they extend polls by providing a real-time feed of probabilities that applies to a wide variety of political events. But their future value to society—and whether they fare better than their predecessors—depends on how well we solve three new governance challenges: manipulation, discovery, and resolution.

Three questions that will make or break prediction markets for politics

Question 1: When markets become narrative, how do we think about manipulation and unintended consequences?

As long as there have been betting markets around elections, there have been people skittish about some of the negative consequences the markets and their manipulation could have for society. There are at least three kinds of market manipulation to worry about.

Becoming targets of influence in society

First, if markets begin to shape how voters, journalists, and elites think about political realities, then people with an incentive to shape those beliefs will naturally try to move the markets themselves.

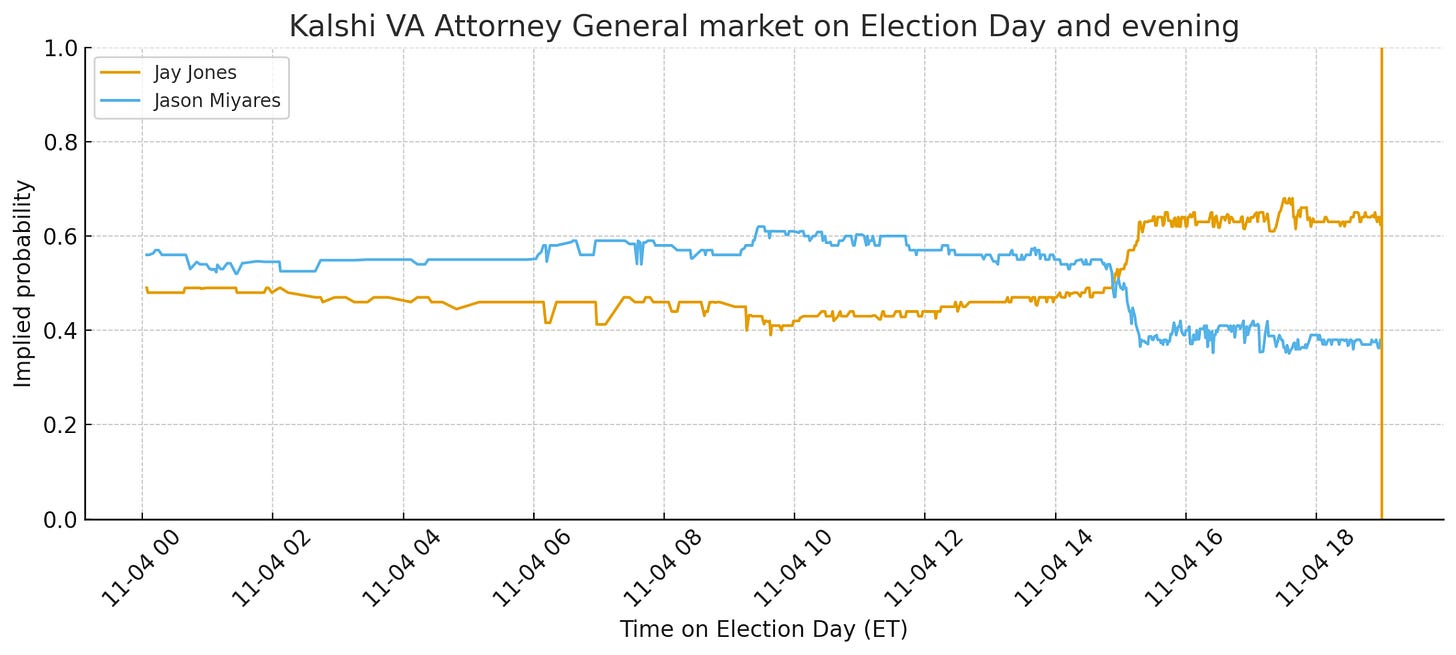

On election night in New York, I saw how this could become important. Early in the day, the Republican candidate for Attorney General in Virginia, Jason Miyares, was leading his Democratic opponent, Jay Jones, in the prediction markets. But in the early afternoon, before any polls closed or any hard election data was available, the markets suddenly started moving, and Jones overtook Miyares, as the price plot below shows.

We were baffled. What were the markets seeing when no election returns were available yet?

The answer as best I can tell turned out to be that people on X were scrutinizing exit polls and, like “@DaysYoungkin” pictured above, also posting deep in the weeds reports regarding turnout in Virginia, which experts believed looked favorable for Democrats in the state. Data like this got reposted by influential elections and prediction market accounts. As Jones’s price started to rise, widely followed prediction market accounts started to post “BREAKING NEWS” alerting everyone to the fact that Jones’s price was swinging, causing more people to come into the market.

All of this, I felt, was the market operating as it should, and intersecting with social media in an interesting and potentially valuable way. But it also raised a specter of how it could go awry. Who were these people purporting to have turnout data for Virginia? How confident are we in extrapolating such data, even if it’s real, to predict the election outcome?

And what would happen if someone started to intentionally post false information about what was going on? It’s easy to imagine a political campaign wanting to make their prospects look more favorable, or a trader wanting to “pump” the price of some candidate before dumping their shares.

As volumes grow into the billions, the incentives to push, distort, or strategically time such signals will increase. And there is precedent. In 2012, someone tried to move Romney’s odds on InTrade, the largest prediction market of that era. In the early 20th century, according to Rhode and Strumpf, newspapers often covered claims regarding manipulation of the electoral betting markets, too.

But here’s why I’m not overly worried about this issue: one person’s manipulation is another’s potential profit. In the Romney case, other traders quickly corrected the mispricing, as Rothschild and Sethi showed in a paper studying the incident. And despite the concerns about manipulation in the betting markets of the early 20th century, they proved to be both popular and accurate.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t pay attention to the risk, though. Today, the information environment is highly fragmented and decentralized, and skepticism about elections is widespread. In such an environment, false claims meant to briefly manipulate a market on election day could wreak havoc.

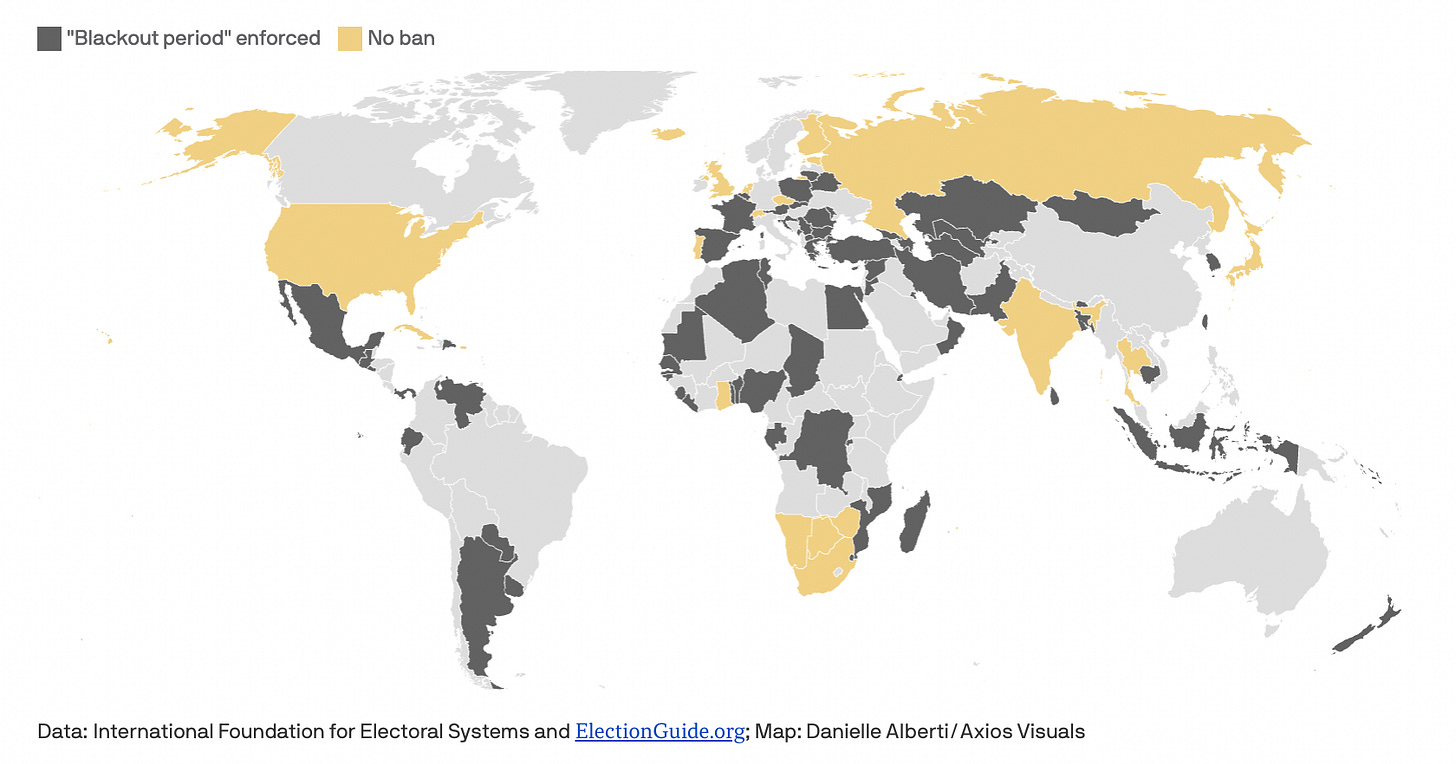

With concerns like these in mind, many countries that have general blackout period rules for elections (see map below) will probably say these laws apply to or extend to prediction markets. I do not think the US could or should implement such a rule. Instead, though, we should make citizens and traders aware of the risk of manipulation and make sure they are duly skeptical of claims they see online that may be intended to move the markets.

Many countries enforce a blackout period on campaigning and election news on and around election day, which they will likely say includes prediction markets.

‘Throwing the game’ and manipulation by insiders

Another kind of manipulation occurs when the subject of a market can act to determine its outcome.

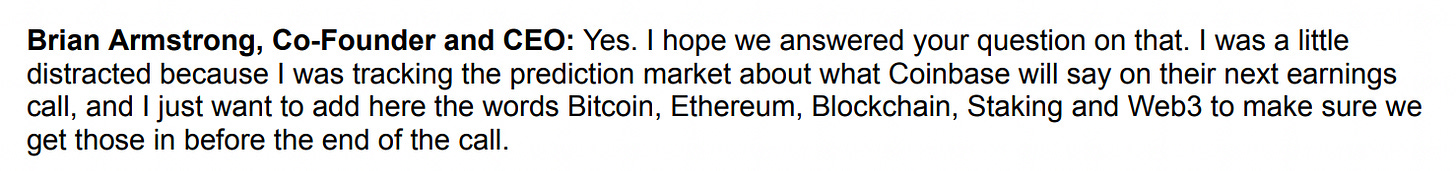

For example, Kalshi and Polymarket often run “mention markets” in which people bet on the words that a famous person will say or not say in public remarks. In a recent earnings call, Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong read out a number of the words people had bet on at the end of his call, as you can see in the transcript here:

In Armstrong’s case it’s a brilliant piece of trolling, but in more serious markets this could threaten their long-term viability altogether, as in the recent NBA-related betting scandal. Participants will not long use a system they believe is rigged or vulnerable to insiders.

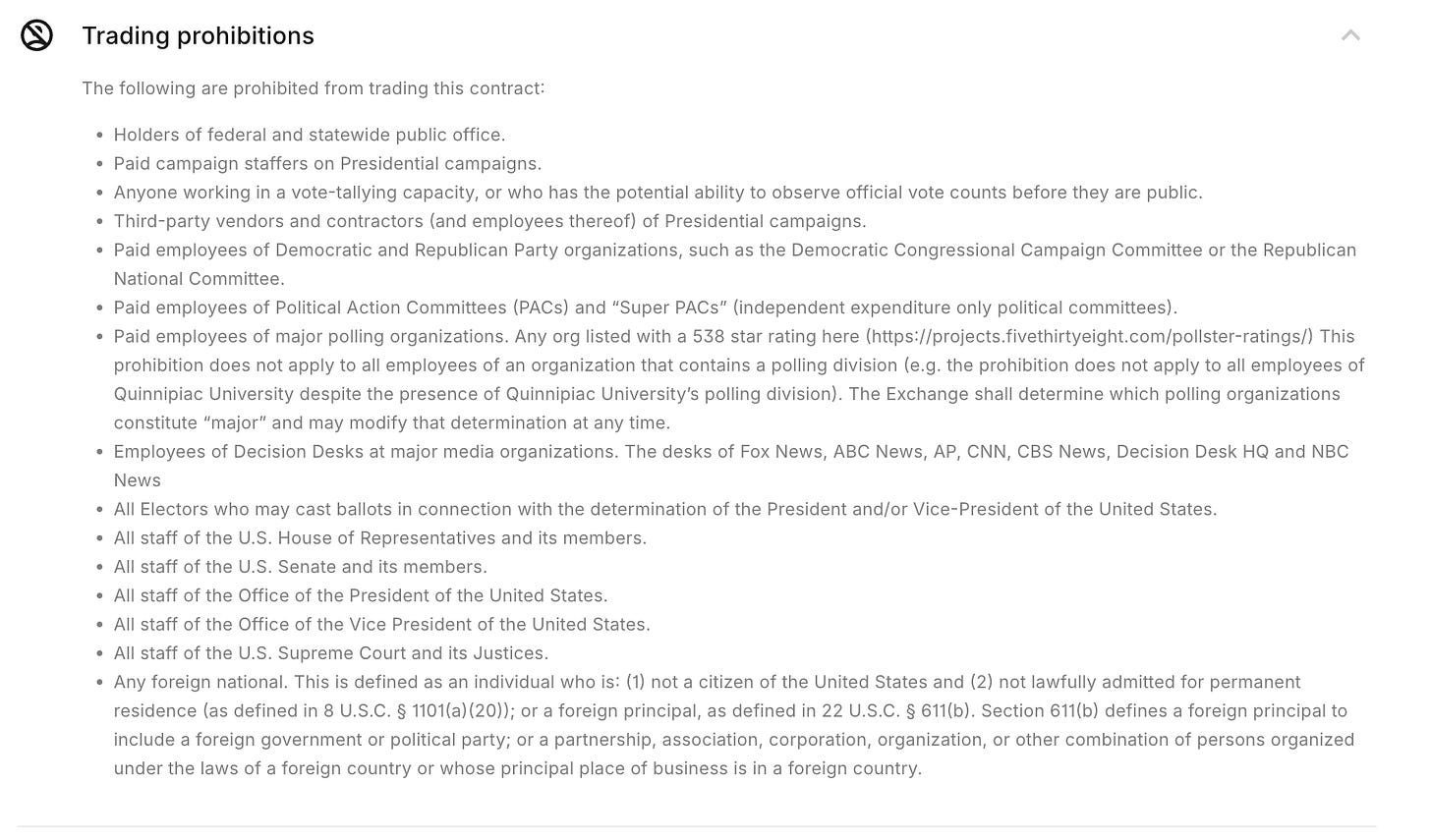

For core election markets, manipulation risk is probably low: it is extraordinarily difficult to alter an actual election outcome at scale, and the political and personal payoff from having the power to do so likely dwarfs anything that could be earned from a market position. But there are also logical steps we can take to keep the risk low, including precluding people involved in the counting of votes from betting in election markets——individuals that Kalshi’s policies already exclude:

But not all contracts are so robust. Mention markets and other easily gamed markets are inherently vulnerable, and I’m bearish on their long-term prospects. If very narrow, specific political markets develop, we should be wary of this problem for them, too.

Self-fulfilling prophecies

A final concern: could predictions become self-fulfilling? If markets signal a candidate is doomed, might voters stay home? While we have some evidence polls affect turnout, I’m doubtful suppressing information helps, on net. And it could backfire if it prevents voters from learning that a race is actually competitive.

I am generally very skeptical that voters are better off having less information rather than more.

Question 2: When we have markets for everything, how do we find the right ones at the right time and make sure they resolve correctly?

One of the things that most surprised me in New York was the challenge of finding all the relevant markets worth betting on. Obviously we had our eye on the simple markets for who would win the mayoral race in New York, the governors’ races in New Jersey and Virginia, and the closely contested VA AG race. But it turns out, there are a ton of other interesting markets, too!

There are markets on the final vote margin for all these races; markets on which of a list of candidates will outperform the others on the list; markets on whether certain candidates will outperform their polling averages; and many, many others. In fact, there are so many interesting contracts already that you can’t view them all on one page, and after election night was over, I discovered a whole host of other contracts I wish we had thought to bet on and to monitor.

As the number of political contracts explodes, the bottleneck won’t just be liquidity, but attention. If prediction markets are going to help us understand a noisy political world, they need to solve a basic question: Which markets should people see first?

This will require better ranking algorithms, smarter UI, and eventually AI agents that understand a user’s interests and surface the right contracts at the right moments——linking them to the news, data, and commentary the user is already consuming. Social discovery matters too, as Nick Ruzicka has pointed out, because people want to coordinate on the same markets as their friends.

Clearly, the way to scale the platform is to allow users to post their own contracts, allowing prediction markets to make sure they offer contracts on everything people are conceivably interested in.

Then comes the harder question: how do we resolve these contracts at scale, at low cost, and with sufficient trust? If it’s already hard to resolve a small number of contentious markets, how would we resolve millions of such markets each month?

Some experimental platforms, like Manifold, provide hints. In Manifold, the creator of a market is responsible for resolving it, using hopefully clear criteria they set out in advance. Trading closes automatically at the deadline, but the market does not pay out until the creator declares an outcome—“YES,” “NO,” a percentage split, or, in rare cases, “N/A.” If a creator disappears or resolves incorrectly, Manifold moderators can intervene, and the community can publicly challenge or dispute ambiguous resolutions. This lightweight, reputation-based system looks a lot like community moderation in social media platforms, and could be an interesting model to build from in the future.

Question 3: When markets are a source of truth, how do we define truth for the most contentious issues?

In the lead-up to election night, we had a strong conviction that Mamdani would easily win the mayoral race, but a small fear nagged at the back of my mind: what if Mamdani won, but didn’t meet the conditions of the contract? The Kalshi contract, for example, stated that it would pay out based on who was “sworn in” as mayor. What if something crazy happened and Mamdani won the election but wasn’t sworn in? Given public discussions of ideas to deport the mayor-elect or to declare him ineligible to serve under the terms of the Insurrection Act, I had to at least consider this edge case possibility, even though the contract ended up resolving just fine in this case.

I had reasons to worry, too, because prediction markets regularly face challenges around how to resolve the most contentious contracts.

Venezuela’s 2024 presidential race offers one such cautionary tale. The government declared Nicolás Maduro the winner while the opposition and international observers alleged widespread fraud. On Polymarket, more than $6 million traded on the outcome, but conflicting rules about whether to follow “official information” or a “consensus of credible reporting” led to chaos. After the market initially priced a Maduro win at roughly 95 percent, the “UMA oracle” that resolves contract disputes on Polymarket ultimately resolved the market for the opposition candidate instead.

The decision sparked a furious debate over what the meaning of “winning” an election is or could be: should it be the person who takes office and is recorded as winning the official vote, or the person that independent monitors believe would have won a free and fair version of the election?

In a world where prediction markets are increasingly seen as sources of truth——many people pointed to when Kalshi “called” the mayoral election in New York City as the proof that Mandani had won——determining these edge cases will be exceedingly fraught.

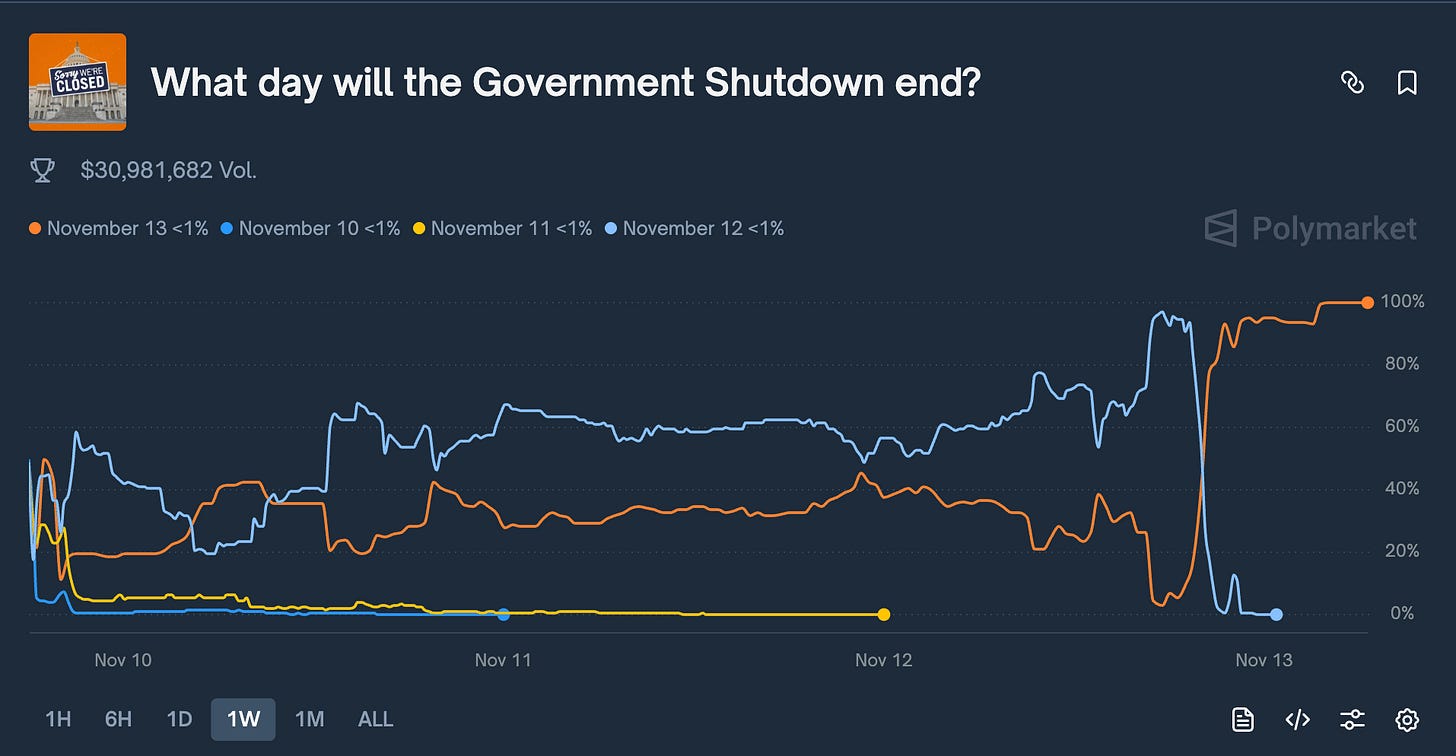

Here’s another crazy case that makes clear the challenge of writing good resolution rules for contracts. If you ask ChatGPT what date the US government shutdown ended, it will tell you November 12th, which is the day President Trump signed the funding bill into law that ended the shutdown. Makes sense.

And for a while, Polymarket agreed. The blue line below shows you that the price for Nov 12th traded close to 100% on the 12th. So why did the price then crash, and why did the market end up paying out to people who bet on November 13th, not 12th?

The answer is that the Polymarket resolution rule stated: “The resolution source for this market will be OPM’s Operating Status page.” And for whatever reason——an unsubstantiated rumor claimed it was because the site administrator was out on a date that night?——OPM’s status page did not get updated until the 13th. D’oh!

The episode highlights how fragile current systems can be. Panels of independent experts, a more robust version of token-based governance that avoids the conflicts of interest and whale-dominance of Polymarket’s UMA-based voting system, or AI-driven resolution are all possible alternatives, but each has serious trade-offs. Building reliable, scalable resolution for contentious political events remains an unsolved—and essential—challenge.

Looking to the future

Back home after my experiment in New York, I’ve developed a new habit. When I watch NFL games, I have the Kalshi and Polymarket prices open on the computer next to me. When I see them spike, I know to pay attention to the game in anticipation of a big play, because the markets move several seconds before my TV feed does. Traders are literally outrunning my “live” TV. The growth and speed of these prediction markets is truly extraordinary.

Real-time prices from political prediction markets can cut through noise, quantify uncertainty, and help us see the world more clearly, if they are designed with care. That means solving at least three linked governance challenges that I’ve explored here: manipulation, discovery, and resolution. There are good reasons to be optimistic about all of them, but they all require careful thought and learning from mistakes as we go. I’ll be sharing more in-depth ideas on each in the coming months.

Disclosures: I receive consulting income from a16z crypto, a venture capital company that recently announced an investment in Kalshi. I also receive consulting income from Meta Platforms, Inc.

Many traders were known to have called the election clerks for live turnout data. Or sometimes they post the data themselves. Unlikely that a manipulation campaign works at all.