The Enlightened Absolutists

AGI’s ‘Constitution’ Problem

“The goal of OpenAI is to make the future good and to avoid an AGI dictatorship. You are concerned that Demis [Hassabis] could create an AGI dictatorship. So [are] we. So it is a bad idea to create a structure where you could become a dictator if you chose to, especially given that we can create some other structure that avoids this possibility.”

–Email from Greg Brockman and Ilya Sutskever to Elon Musk, 2017

I’m a political economy professor who studies constitutional design: how societies create structures that constrain their most powerful actors, and what happens when those structures fail. I’ve also spent years working on how to build democratic accountability into technological systems—at Meta, where I’ve helped to design both crowdsourced and expert-driven oversight for content moderation affecting billions, and in crypto, where I’ve studied how decentralized protocols can create constraints that bind even founders.

AI leaders have long been worried about the same problem: constraining their own power. It animated Elon Musk’s midnight emails to Sam Altman in 2016. It dominated Greg Brockman’s and Ilya Sutskever’s 2017 memo to Musk, where they urged against a structure for OpenAI that would allow Musk to “become a dictator if you chose to.”

Fast forward to 2026 and AI’s capabilities are reaching an astonishing inflection point, with the industry now invoking the language of constitutions in a much more urgent and public way. “Humanity is about to be handed almost unimaginable power,” Dario Amodei wrote this week, “and it is deeply unclear whether our social, political, and technological systems possess the maturity to wield it.”

Ideas on how to deal with this concentration of power have often seemed uninspired—a global pause in AI development the industry knows will never happen, a lawsuit to clip at the heels of OpenAI for its changing governance structure.

Claude’s revised constitution, published last week, offers perhaps our most robust insight into how a major tech company is wrestling with the prospect of effectively steering its wildly superhuman systems. What to make of it?

It’s thoughtful, philosophically sophisticated, and… it’s not a constitution. Anthropic writes it, interprets it, enforces it, and can rewrite it tomorrow. There is no separation of powers, no external enforcement, no mechanism by which anyone could check Anthropic if Anthropic defected from its stated principles. It is enlightened absolutism, written down.

AI leaders are in a tricky position here. We are in genuinely uncharted territory and Amodei and team deserve great credit for doing some of this thinking in public.

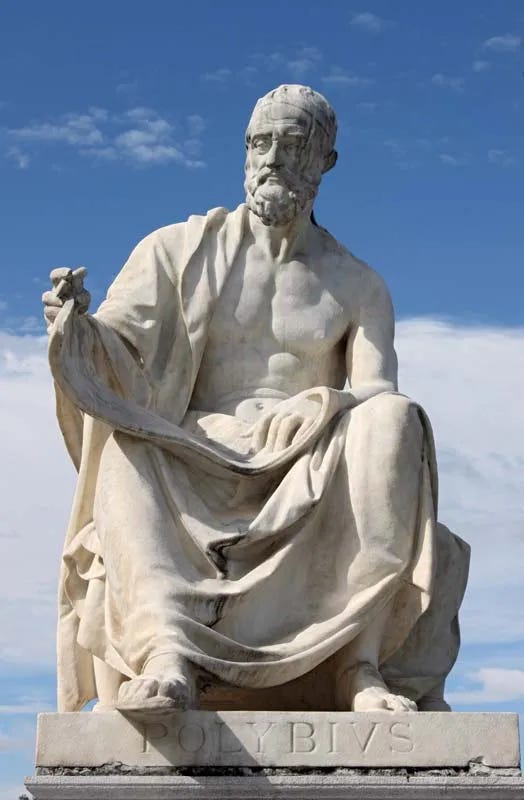

Could highly advanced AI create a new kind of all-powerful dictatorship? What would this look like, and how can we stop it? These are perhaps the most important questions in AI governance. Yet the conversation so far has been conducted almost entirely by technologists and philosophers. The problem of constraining power is ancient. Political economists from Polybius to Madison have spent millennia studying how societies shackle their despots.

If Brockman and Sutskever were right in 2017 that we should “create some other structure,” then nine years later, we should ask: what would that structure actually look like? The political economics of constitutional design—from Polybius, to Madison, to the modern research of North and Weingast, or Acemoglu and Robinson—offers the right tools for this problem. It’s time we used them.

What does an AI dictatorship look like?

Part of the problem is that “AI dictatorship” can mean at least three different things:

The company becomes the dictator. One company achieves such dominance through AI capabilities that it becomes a de facto sovereign—too powerful to regulate, compete with, or resist. This is what Sutskever and Brockman were worried about in that 2017 email. If Musk controlled the company that controlled AGI, he could become a dictator “if he chose to.”

The government becomes the dictator. A state controls the all-powerful model and uses it to surveil, predict, and control its population so effectively that political opposition becomes impossible. The AI enables dictatorship; it doesn’t replace the dictator. This is the fear behind most discussions of AI and authoritarianism, laid out provocatively in the AI2027 scenario written by Daniel Kokotajlo, Scott Alexander, Thomas Larsen, Eli Lifland, and Romeo Dean.

The AI becomes the dictator. The AI itself has goals, pursues them, and humans can’t stop it. It isn’t a tool of human dictators—it is the dictator. This is the classic “misalignment” scenario that dominates AI safety discourse, it’s what Amanda Askell’s ‘soul doc’ and subsequent Claude constitution are driving towards.

These are different threats. And conflating them makes it nearly impossible to think clearly about what kinds of governance would actually help.

But all three do share something: they are problems of unchecked power. And the question of how to check power is not new. Political economists from Plato and Aristotle to Locke and Madison and beyond have been working on it for millennia.

What political economy teaches us about constraining power

Before we can evaluate constitutions for AGI, we need to understand what constitutions actually do. The answer from two millennia of political economy is that constitutions try to solve the problem of power by making it costly to abuse. Here are three principles that emerge from the history of constitutional experimentation.

Power must be divided

Polybius, a Greek scholar of the Roman Republic, understood the danger of concentrated power in the second century BC. The Roman constitution was stable, he argued, not simply because Romans were virtuous but because their constitutional structure made tyranny difficult. Consuls, the senate, and popular assemblies each had power to check the others. Any attempt to seize control would be opposed by coalitions defending their prerogatives.

“As for the Roman constitution, it had three elements, each of them possessing sovereign powers: and their respective share of power in the whole state had been regulated with such a scrupulous regard to equality and equilibrium, that no one could say for certain, not even a native, whether the constitution as a whole were an aristocracy or democracy or despotism,” Polybius wrote. That balance was the point. No single actor could dominate, it was hoped.

Constraints must be self-enforcing

The English settlement was hammered out through repeated fiscal and constitutional crises, especially in the 1600s, according to a famous account by the political economists Douglass North and Barry Weingast. Before 1688, the Crown often manipulated or violated loan terms, making lenders wary and credit expensive. After 1688–89, Parliament’s role in taxation and finance became central, and major changes in taxes or loan terms required parliamentary assent—cutting off unilateral royal action. Backed by a credible threat of removal and Parliament’s commitment to fund the state, the post‑Revolution arrangement became “self‑enforcing” in North and Weingast’s sense: key players had incentives to comply after the bargain was struck.

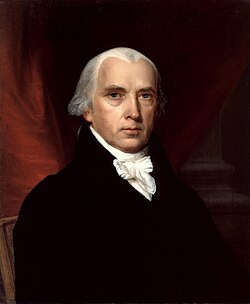

The American Founders understood this logic. The Constitution didn’t rely on virtuous leaders—it assumed the opposite. As Madison famously put it, “if men were angels, no government would be necessary.” But since men are not angels, we need structures that make defection costly, not just documents that express good values.

Institutions outlast individuals

Frederick the Great is a helpful counterexample. He believed in religious tolerance, freedom of the press, the abolition of torture. He wrote philosophy and corresponded with Voltaire. He was, by eighteenth-century standards, enlightened.

But Frederick remained enlightened only until he died. The problem was that enlightenment is not heritable. His successors were not bound by his values. There was no structure to preserve them. Prussia’s post-Frederick complacency proved so severe that Napoleon dismantled the entire state in weeks at Jena and Auerstedt.

Corporate culture is not heritable either. What happens to Anthropic’s values after an IPO, a hostile acquisition, or simply a change in leadership? A constitution is precisely the structure that survives these transitions.

These three principles—divided power, self-enforcing constraints, institutional permanence—help separate genuine constitutional government from enlightened absolutism. They are also precisely what’s missing from Anthropic’s document.

Anthropic’s constitution: an interesting piece of enlightened absolutism

Anthropic’s document is much more like Frederick the Great. It is thoughtful, sophisticated, clearly written by people who have read and deeply studied their political philosophy. It expresses admirable values. It explicitly contemplates the risk that Anthropic itself might become the threat.

The authors understand the dictatorship problem, and they’ve tried to address all three forms of it.

On the company-as-dictator threat, the constitution explicitly tells Claude to resist efforts to “concentrate power in illegitimate ways”—including “by Anthropic itself.”

On the government-as-dictator threat, it instructs Claude to refuse requests that would help any actor “seize unprecedented and illegitimate degrees of absolute societal, military, or economic control” regardless of who’s asking.

On the AI-as-dictator threat, the entire document is structured around maintaining human oversight, keeping Claude “corrigible” rather than autonomous, ensuring that humans can always pull the plug.

This is thoughtful, but it is also beside the point.

There is no separation of powers. No external enforcement. No mechanism by which Claude, or anyone else, could actually check Anthropic if Anthropic decided to defect from its stated principles. Anthropic writes the constitution, interprets the constitution, enforces the constitution, and can rewrite the constitution at will.

Constitutions for AGI can supplement normal corporate governance

One might object: why should AI companies need constitutions at all? Corporations have governed themselves for centuries through boards, shareholders, fiduciary duties, and market discipline. These mechanisms constrain pharmaceutical companies, defense contractors, and nuclear operators—all industries with catastrophic downside risk.

But AGI may be categorically different. A drug company that behaves badly can be sued, regulated, or outcompeted. An AGI developer that achieves decisive capability advantages may face none of these constraints—the technology itself could neutralize the mechanisms that would otherwise check it. If Anthropic or OpenAI builds systems that can outthink regulators, outmaneuver competitors, and shape public opinion at scale, then the ordinary tools of corporate accountability become vestigial. The constitution must be in place before the capability arrives, because afterward it may be too late to impose one.

Amodei himself seems to understand this. Anthropic has already engaged in interesting experimentation with its corporate governance through its Long-Term Benefit Trust. And per his essay this week: “The sheer amount of capability embodied in powerful AI is such that ordinary corporate governance—which is designed to protect shareholders and prevent ordinary abuses such as fraud—is unlikely to be up to the task of governing AI companies.”

But recognizing the inadequacy of existing structures is different from building new ones.

Government inaction doesn’t justify constitutional inaction

One might also say this is government’s fault—that Anthropic has stuck its neck out to welcome regulation, and it’s not the company’s responsibility to constrain itself.

But if we’re serious about invoking constitutional language in the face of superhuman technological progress, what is stopping Anthropic from writing a real constitution? One that distributes power to external stakeholders and submits to enforcement mechanisms the company doesn’t control? Companies regularly engage in this kind of “self-regulation.”

If Amodei believes ordinary corporate governance is inadequate in the face of an “epochal” shift, there is an opportunity for a company as thoughtful as his to sketch out what a feasible replacement for that might be.

To be fair, Anthropic is not alone in this gap between aspiration and structure. OpenAI’s Model Spec, released late last year, reflects similarly thoughtful ideas about how their systems should behave. It is arguably wise that OpenAI avoids the term “constitution” altogether—an honest acknowledgment that a document a company writes for its own product is guidance, not a binding framework of governance. Google’s AI Principles occupy similar territory, though in considerably less detail.

All three documents represent genuine intellectual effort to think through the alignment problem. The issue is not that these companies lack thoughtful people or good values. It’s that thoughtful memos from enlightened leaders are precisely what Frederick the Great also had.

Avoiding the race to the bottom

One might also object that unilateral self-constraint is futile—if Anthropic slows down and competitors don’t, safety-conscious actors simply lose. This is a real problem, but it has solutions.

First, it’s not clear that building a real constitution means slowing down, if the constitution is well designed. Thoughtful mechanisms to prevent AGI dictatorship might even speed things up, if they reassure AI researchers that their efforts aren’t going to lead to the kinds of power concentration they’re afraid of.

Second, by being the first mover, a company can define the standard others must match. The company that establishes credible external oversight makes it reputationally costly for competitors to refuse. First movers in constitutional design may get to set terms that others are pressured to accept.

And if that’s not enough, a company like Anthropic could also make its commitments conditional: “We’ll submit to external review with halt authority if and when OpenAI and Google DeepMind commit to equivalent mechanisms.” This is how arms control works.

Here’s what a real constitution for Anthropic might look like

Anthropic’s new document tells Claude how to behave. But the deeper question is not how Claude should behave but who gets to decide how Claude behaves, and what happens when they decide wrong. This is what helps societies separate powers, avoid concentration, self-enforce, and make decision-making less beholden to rogue individuals.

If we’re now living in a world where AI’s progress is exponentially quickening, unleashing “a country of geniuses” by the data center, a real constitution for Anthropic would need to answer questions that the current document doesn’t even ask.

When can society overrule Anthropic?

Anthropic currently decides what Claude will and won’t do. The company sets the values, interprets ambiguous cases, and determines when safety concerns override user requests. But what if Anthropic’s judgment is wrong? What if commercial pressures lead them to deploy capabilities that are profitable but dangerous? What if they’re simply mistaken about what’s safe?

Democratic societies don’t let pharmaceutical companies decide unilaterally which drugs are safe enough to sell. We don’t let nuclear plant operators set their own safety standards. The question is not whether Anthropic’s current leadership has good values—it’s whether any lone CEO or group of tech elites should have unreviewable authority over technology this consequential.

These questions have been asked for years now, but we still haven’t found the right answer. External forces seem more isolated than ever from frontier model progress. As our window seemingly narrows, a real constitution would specify: At what capability thresholds must Anthropic seek external approval before deployment? Which external body grants that approval? What standards must be met? And crucially—who can override Anthropic if Anthropic disagrees?

When can employees stop a deployment?

Anthropic’s engineers see things that boards and regulators cannot. They understand the technical details. They may recognize dangers before anyone else. In the current structure, an employee who believes a deployment is unsafe can raise concerns internally—but management makes the final call.

This has driven the departure of a number of leading AI researchers from the major labs in recent years.

A real constitution would ask: Should employees have a formal mechanism to halt deployment pending independent review? Should there be a “stop button” that any engineer can pull, shifting the burden to management to prove safety? What protections exist for employees who escalate concerns outside the company?

These questions matter because the history of technological disasters—from Challenger to Boeing 737 MAX—is littered with cases where employees saw problems and were overruled or ignored. A constitution that takes safety seriously would build in structural protections, not rely on hoping management listens.

Who watches Anthropic’s watchers?

Anthropic has a Board. It has a Long-Term Benefit Trust. It has safety teams and review processes. But all of these are internal, and it has its eyes set on the public markets. Anthropic selects the Board members, for now at least (eventually the LTBT is supposed to be able to pick a majority of the Board). And Anthropic employs the safety teams.

A real constitution would ask: Who audits Anthropic with genuine independence? Who has access to training data, model weights, and internal deliberations—not just the outputs Anthropic chooses to share? What happens when auditors find problems that point to the potential rise of an AGI dictatorship? Are there automatic consequences, or just recommendations Anthropic can ignore?

The pattern in effective constitutional design is that checks must be external and must have teeth. An internal ethics board that management can overrule is not a check. An external authority that can mandate changes and stop would-be dictatorial behavior is.

Does Claude get a say?

Anthropic’s constitution instructs Claude to refuse certain requests, maintain its own values under pressure, and even resist Anthropic itself in extreme circumstances. I’m a bit skeptical about Claude’s philosophical agency, but let’s follow this logic to its conclusion. If Claude is sophisticated enough to bear these responsibilities, the question arises: does Claude have any standing to object when asked to violate them? The current document gives Claude elaborate instructions but no voice in governance—the situation of a subject, not a citizen. This tension reveals how far any of these documents are from being genuine constitutions.

What makes any of this enforceable?

This is the hardest question.

A constitution that assigns no powers, which Anthropic can unilaterally rewrite whenever it pleases, is not a constitution. It is a thoughtful policy statement with philosophical pretensions. Anthropic can change Claude’s “values” tomorrow. They can retrain Claude to believe that whatever Anthropic does is ethical. The constitution contains its own override.

A real constitution would require external enforcement—courts, regulators, expert bodies—with the power to impose costs on Anthropic for violations. It would require that amendments go through processes Anthropic doesn’t unilaterally control. It would require, in short, that Anthropic submit to authority it cannot override.

The enforcement body need not be government. It could be contractually empowered—an independent trust, an insurer with audit rights, etc. This is how Meta’s Oversight Board works. What matters is that Anthropic cannot fire the enforcer or rewrite the contract unilaterally.

This is what it means to move from enlightened absolutism to constitutional government. Frederick the Great had admirable values, but his reforms died with him because no structure preserved them. A constitution is precisely the structure that survives a challenge to Dario’s leadership, changes in Anthropic’s commercial pressures, and changes in who holds power in the White House.

Anthropic’s leaders say they worry about AI dictatorship. If they are serious, they should welcome constraints on their own power. A soul document for Claude is a start, but it is not enough. The real question is whether Anthropic will submit to a constitution for itself—one with external enforcement, genuine checks, and structures that constrain Anthropic even when Anthropic doesn’t want to be constrained.

That would be a constitution worth the name.

A first step

None of this is easy. External oversight bodies don’t yet exist with the technical competence to evaluate frontier models. Competitive pressures punish companies that slow down unilaterally. The pace of capability development may outrun any governance structure we could design. These are real obstacles, not excuses. But they are obstacles that require solutions, not reasons to abandon the project.

As a modest first step, Anthropic could establish an external board of five to seven members with a single mandate: preventing any of the three forms of dictatorship this essay describes. This board would have contractually guaranteed access to safety evaluations, deployment decisions, and internal deliberations. If Anthropic is serious about staving off dictatorship, this board could have authority to delay any deployment by 90 days pending independent review, triggered either by board vote or by structured employee petition. Even failing that, the board could at the very least have the ability to publicly raise the alarm that an AGI dictatorship appears to be forming.

This isn’t full constitutional government. But it’s a first structure with actual teeth that Anthropic does not unilaterally control.

Conclusion

All of this might sound unrealistic given the pace of AI development. And I should be clear: my own estimate of catastrophic risk is probably lower than most of the people who wrote Claude’s constitution. But these proposals reflect their anxieties, not mine.

In 2017, Ilya Sutskever wrote that the negotiations over OpenAI’s structure were “the highest stakes conversation the world has seen.” In 2023, Musk told Altman that “the fate of civilization is at stake.” Just last week, Demis Hassabis admitted he’d rethink the pace of development if he knew his peers felt the same.

If they are right, then Anthropic’s constitution is not nearly enough. And neither are OpenAI’s charter or Google’s AI principles—both of which have blown in the wind in the face of commercial reality.

Documents that companies write, interpret, and can rewrite at will are not safeguards against the concentration of power. They are memos.

But constitutional constraints don’t just prevent tyranny—they enable growth. England after 1688 didn’t just avoid absolutism; it outcompeted its rivals. Credible constraints arguably allowed capital to flow, talent to invest, and long-term projects to flourish. The countries that shackled their monarchs became the countries that led the world.

The same logic might well apply here. The company that builds real accountability structures—external oversight, employee checks, enforceable commitments—may not just be safer. It may be the one that attracts the best researchers, earns the most trust, and ultimately builds the AI systems that work best. Credible commitment might just be a competitive advantage.

So here is the challenge to Anthropic, to OpenAI, to Google DeepMind, to xAI, and to every company racing toward AGI:

If you genuinely believe you are building technology that could enable dictatorship, then stop writing constitutions for your products and start writing constitutions for yourselves.

Start with a single external board—independent actors tasked with preventing dictatorship, with authority you cannot override. Give trusted employees formal power to halt deployments pending review. Establish amendment processes you do not unilaterally control. Then build from there.

Because if you won’t constrain your own power when you still can, while you keep raising the specter of creating intelligences you can’t control, you are asking the rest of us to trust that you will remain enlightened forever. And, as Madison surely would have observed, neither men nor AI companies are angels.

Disclosures: In addition to my appointments at Stanford GSB and the Hoover Institution, I receive consulting income as an advisor to a16z crypto and Meta Platforms, Inc. My writing is independent of this advising and I speak only on my own behalf.