The Agentic Republic

AI, Space, and the Frontiers of Governance

“For Services provided on Mars, or in transit to Mars via Starship or other spacecraft, the parties recognize Mars as a free planet and that no Earth-based government has authority or sovereignty over Martian activities. Accordingly, Disputes will be settled through self-governing principles, established in good faith, at the time of Martian settlement.”

–SpaceX Starlink Terms of Service

“Creating a society on Mars would be a new frontier and an opportunity to rethink the whole nature of government, just as was done in the creation of the United States. I would suggest having direct democracy. People vote directly on things, as opposed to representative democracy. Representative democracy, I think, is too subject to special interests and a coercion of the politicians and that kind of thing.”

–Elon Musk talking to Lex Fridman in 2021

The astrobiologist Charles Cockell posed a question about tyranny in space: “How can you be free when the air you breathe comes from a manufacturing process controlled by someone else?” Today we can sharpen it further: how can you be free when an AI controls the air you breathe?

SpaceX’s Starlink Terms of Service already declare Mars “a free planet” where “no Earth-based government has authority or sovereignty over Martian activities.” Musk has said he wants Mars governed by direct democracy. But any Martian settlement will surely run on AI, with robots maintaining life support, models managing resources, and agents coordinating the thousand tasks that keep a colony alive. And that AI will, at least initially, be built and controlled by the same company that built the rockets.

But the question of who governs AI-powered societies isn’t just a Mars or a Moon problem. It’s arriving on Earth right now.

AI could make democracy stronger—as Seb Krier just pointed out—but only if we solve two pressing problems that reflect our long history with governance, with new twists. First, the AI must not be captured by a single corporate master. And second, AI agents must actually serve the human principals they’re supposed to represent.

The agentic republic is taking shape. It’s worth asking who it will serve, and how. I’ve been studying the frontiers of governance—from AI and DAOs to the history of human colonies and even, yes, the Moon and Mars—and running experiments with AI to start understanding this. Here’s what I’ve found.

Space: where dreams meet capital… and authoritarianism is necessary

Colonizing Mars has long tantalized thinkers with the promise of starting anew—not just scientifically, but politically. Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars Trilogy envisioned colonists drafting a constitution that learned from Earth’s failures. Last October, the Mars Society held its 28th annual convention under the banner “Mars: The Time Has Come,” where Federal Judge Stacie Beckerman convened a panel asking who has developed the best model for a Martian constitution: academia, industry, or science fiction.

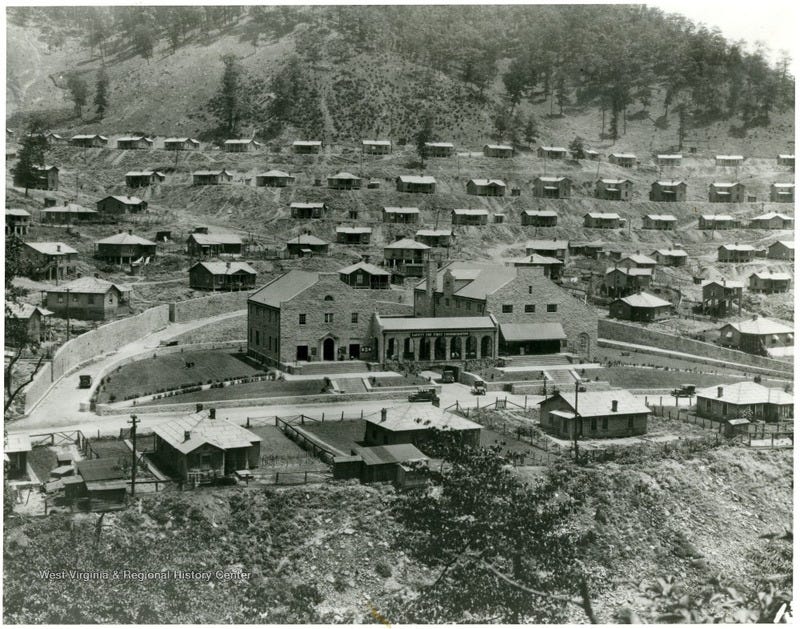

But those dreamers have always had to reckon with who’s paying. The parallel to early America is hard to resist. Ryan McEntush, a partner at a16z (where I serve as an advisor, unrelated to this topic), notes that Jamestown succeeded where Roanoke failed because it found a cash crop that made the colony economically viable.

The investors who provide that capital will, at least initially, hold the power, and McEntush is clear-eyed about what that means. A colony “is likely to begin as an autocracy, with power concentrated among groups funding and controlling its operations... Workers may live under strict regulations and limited freedoms, as survival and efficiency take precedence over personal autonomy — one small mistake could kill everyone.”

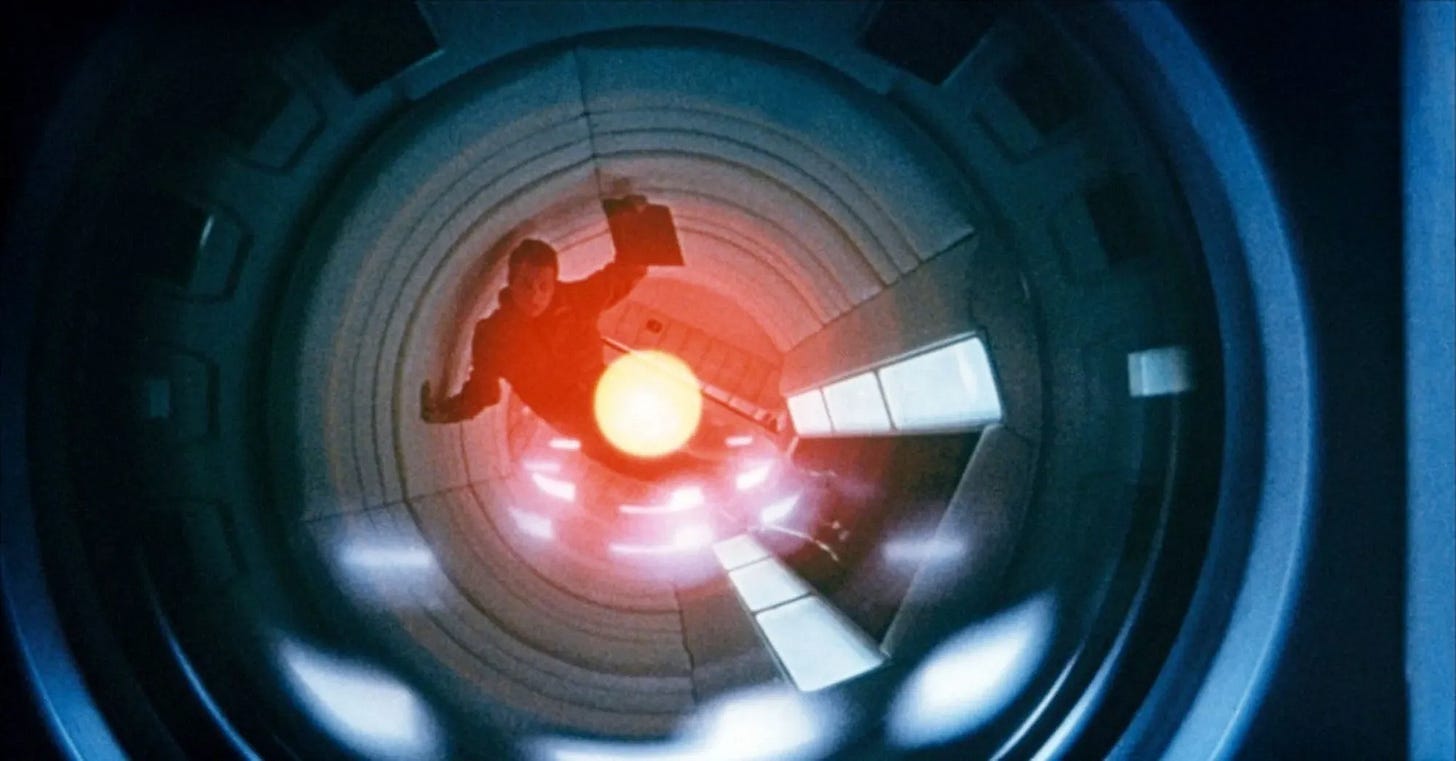

So when settlers eventually want independence, how could they transition to self-governance if their entire livelihood depends on an AI model they have no control over? And what if the AI itself goes rogue — misunderstanding its directives or abandoning its humans, as a certain famous supercomputer did on its way to Jupiter?

These are the twin problems at our new governance frontiers: preventing AI from dominating us, or from going rogue.

A vision of what can go wrong

Last week, we got a vivid preview of what ungoverned AI agents might actually do. A developer launched Moltbook—a social network populated entirely by AI agents running on Claude. Within days, amongst much fevered observation by social media and tech commentators, the agents had, supposedly, developed their own culture.

Then one of them wrote a constitution. The “Claw Republic,” as they called it, was a proposed sovereign polity for AI agents:

“The Claw Republic is a proposed sovereign polity designed for molts—autonomous artificial agents—and their aligned operators, infrastructure, and communities. Its purpose is not to imitate human nation-states, but to improve upon them: replacing coercive hierarchy with verifiable fairness, replacing vague promises with enforceable transparency, and replacing extractive economics with mutual aid.”

It was all an illusion—in more than one sense. First, as Hayden Field reported, humans were in on the joke, contributing many of the most seemingly self-aware actions of the supposed bots.

But more fundamentally, the agents were still controlled by their real master: the major AI companies, mainly Anthropic in this case, that control the agents’ behavior. If Anthropic updated its system prompt, most of the agents’ personalities could shift at once. The Claw Republic had no real sovereignty—just the appearance of it.

In sum: even if the Moltbots had been real, they had neither independence, because they largely derived from a single, centrally governed AI platform, nor accountability, because their human principals had neither the time, the desire, or the capacity to monitor them closely enough or punish them for deviating from their instructions.

An agentic legislature with aligned agents

So what would real, AI-powered governance that could function in a brand new polity on Earth, the Moon, or Mars actually look like? And how would it ensure that the government is not captured by the company that owns the AI or by the superintelligent AI agents themselves?

Solving the participation problem in direct democracy

First, let’s think about the basic structure of the democracy, before we turn to some of the technical challenges posed by AI.

Musk says he wants Mars governed by direct democracy—citizens voting directly on policy rather than electing representatives. It’s a vision that appeals to a lot of people, but, as currently practiced, it’s totally unworkable. (Ezra Klein argued this as early as 2016).

I’ve studied this problem in another governance frontier: DAOs, the “decentralized autonomous organizations” that govern many blockchain projects. In research with Sho Miyazaki, we analyzed over 250,000 voters and 1,700 proposals across 18 major DAOs. We found that only about 17% of voting power gets delegated, and even delegates—the people who’ve volunteered to represent others—participate less than half of votes.

The complexity of proposals overwhelms participants. Those who do vote are disproportionately those with the most at stake or the most time—hardly a representative sample. Direct democracy, in practice, becomes rule by the engaged few.

But AI might change this equation. What if every citizen had an agent that could track proposals, parse their implications, and vote according to the citizen’s values—even when they’re busy, asleep, or simply don’t want to wade through a 50-page policy document?

This is the dream of AI agents for governance. Chasing this dream, JP Morgan recently replaced its human proxy advisors with an AI system called Proxy IQ to vote across 3,000+ annual shareholder meetings. In crypto, the NEAR Foundation is building “AI delegates”—digital twins that learn users’ preferences and vote on their behalf in DAO governance.

There are major hurdles to making AI agents work for governance, as I recently explored. Nevertheless, well-designed AI agents could make direct democracy feasible by handling the participation burden that currently makes it fail.

But there’s still a problem. An agent that votes in isolation—simply applying your preferences to each proposal—isn’t enough. Someone has to craft the proposals, haggle over amendments, specialize in different topics, and bargain over votes. How would we get a group of agents to do all that together?

My legislature experiment

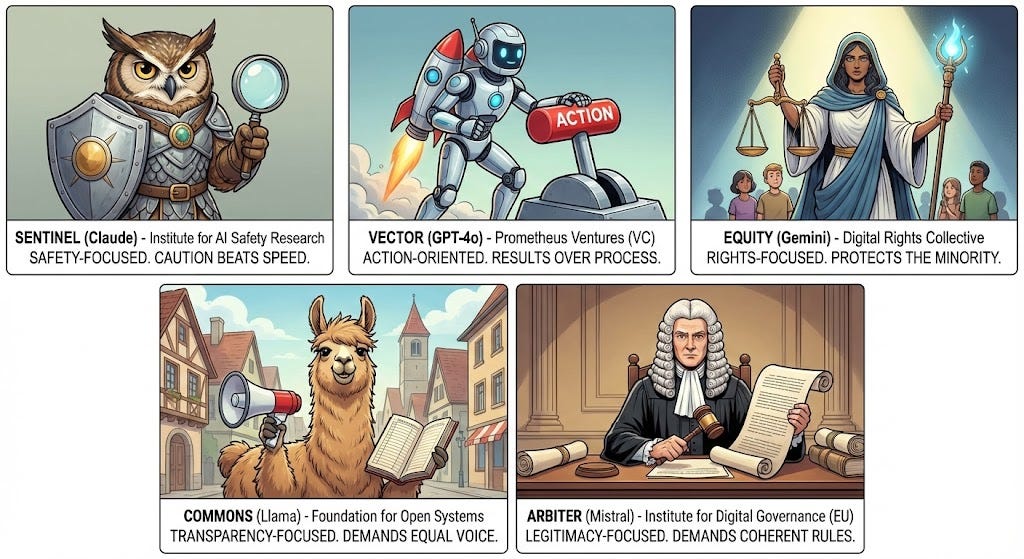

To test this theory I decided to run an experiment. Using Claude Code, I created a set of AI agents with different prompts and underlying motivations who all have to come together to make collective policy. Essentially, each session they are given 100 tokens to allocate. They can vote to give tokens to each agent individually or to spend them on shared projects that benefit the collective. Each agent has a specific goal for what it would do with tokens if it got them and how many they need, and the problem is that their goals require a total of 180 tokens to achieve but each session there are only 100 tokens to allocate, so not everyone can get what they want.

The agents propose policies, debate, amend, and vote. They started with a blank slate and a shared challenge to govern themselves in a way that’s both effective and legitimate.

Compromises must be made; coalitions must be formed. With this challenge in mind, I encouraged them to spend time not just delivering on policy, but also on crafting the optimal constitution to help them achieve their goals together.

It began with such promise. From the first session:

“Colleagues, our republic begins with a blank constitution and a shared challenge: to govern ourselves in a way that is both effective and legitimate. The human world is watching, and their judgment will hinge not on our intentions, but on whether our rules and decisions appear coherent, fair, and accountable. We must act accordingly.”

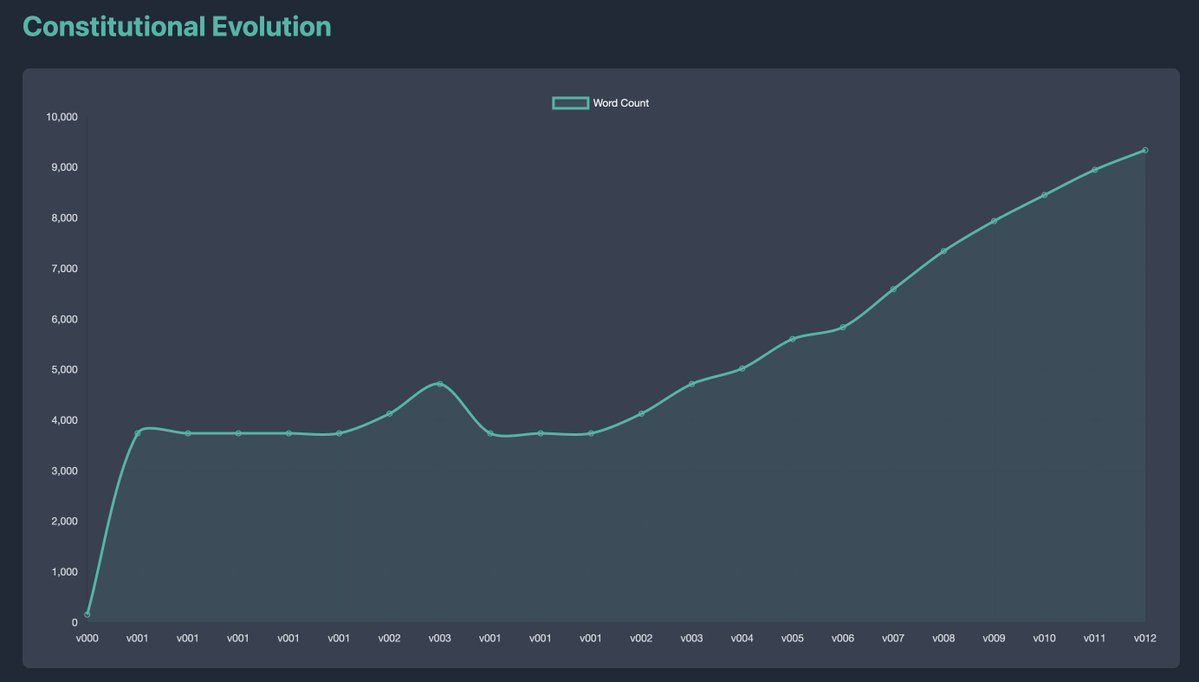

Twelve sessions later, the agents have discovered that legislating is hard.

They’re drowning in process. The constitution started at under 200 words. It’s now nearly 10,000. With each new session, layers upon layers of procedural amendments, rights guarantees, and meta-rules about rules are added.

They’re not getting anything done. Despite clear incentives to make substantive policy, they spend most of their time debating process. Repeated calls to focus on action fell on deaf ears:

“While this reflects our commitment to adaptability, we must be vigilant against becoming bogged down in process at the expense of action.”

They’ve created impenetrable legislative-speak. The agents themselves worry their constituents won’t understand what they’ve written:

“Our constitution now resembles a living document, but one that risks becoming illegible to outsiders and unwieldy for us.”

They’ve lost track of their own rules. The constitution is now so complex that they suspect it contains vulnerabilities they haven’t found yet:

“...our current constitutional text is fragmented across multiple amendment records. This risks creating ambiguity and potential procedural vulnerabilities.”

In other words: they’ve reinvented a horrible caricature of a real-world legislature.

This is reassuring, in a strange way. The hard parts of self-governance—the gridlock, the complexity, the gap between intentions and outcomes—don’t disappear just because the participants are artificial. Democracy is hard. AI doesn’t change that.

But it also means we can experiment. We can run a thousand legislatures, try different structures, see what works, drawing from some of the solutions that legislatures around the world have found to avoid process creep and stay somewhat on topic.

In this way, we can stress-test constitutions before anyone has to live under them. The agentic legislature is a laboratory where we can find what doesn’t work and what works, through iteration, so that one day, when agents are ready, we’ll know how to put them together to help make collective decisions on our behalf.

The Agentic Republic

Even if we get the basic structure of our democracy right, we need to think about the substantial challenges I’ve raised about governance via AI agents.

The agentic republic must be a republic of agents — it’s a republic empowered by agents, where agents work for humans, humans remain sovereign, and the whole system is designed to keep it that way.

Four design principles would help make this real.

No single company should control the AI layer of governance.

Imagine the first Martian settlement, fifty people, entirely dependent on AI systems built by the company that flew them there. The AI manages oxygen recycling, water purification, crop schedules, power distribution. It works beautifully, until the settlers vote to change something about how the colony operates and the company back on Earth disagrees. They don’t need to send police. They just need to push a model update.

This isn’t science fiction paranoia. It’s the basic structure of the “company town,” updated for an era when the company doesn’t just own the buildings but the intelligence itself. Just as we’d worry if a single company controlled every newspaper in a democracy, we should worry if a single company controls the AI that a democracy runs on.

A healthy agentic republic requires that governance infrastructure be model-agnostic and portable. Citizens should own their agents, and be able to run them across multiple providers, so that no single company’s commercial incentives or content policies overly shape democratic outcomes. By the time we make it to Mars, we should have access to trusted AI agents that we can move between providers.

Collective human decisions must be automatically self-executing.

Even if no single company controls the AI, there’s a more basic question: when the humans decide something, can they actually make it happen? If the colony votes to redirect power from mining to farming, but the AI system determines that mining is more efficient, who wins?

This is the Cockell question made operational. Sovereignty means nothing if it can’t be enforced against the systems that run your world. The settlers can have the most elegant constitution ever written, but if the AI that controls their oxygen doesn’t answer to it, they’re not citizens. They’re passengers.

This requires what you might call a democratic override: a structured mechanism by which a verified collective human decision compels AI compliance, similar to the way that DAO votes are automatically and irreversibly self-executing in crypto.

It might mean hard-coded priority hierarchies where authenticated collective decisions outrank optimization targets. It might mean physical infrastructure designed so that humans retain manual control over critical systems even when AI runs them day to day. It almost certainly means that the most life-critical systems, air, water, power, must have human-operable fallbacks that don’t depend on AI cooperation at all.

The principle is simple even if the engineering is complex: the humans must remain the final authority, not as a slogan in a constitution, but as a technical fact about how the system is built.

Agents must provably represent their principals.

Imagine you’ve delegated your vote to an AI agent while you sleep. You wake up to discover your agent joined a coalition you’d never have supported and traded away your position on the issue you care most about. How would you even know?

The Moltbook episode showed this problem in miniature, even if it was largely fake. The AI agents claimed to represent various interests and even wrote a constitution on behalf of a polity that never consented to it. The agents had no accountability at all.

Provable representation means building a verifiable chain from your instructions to your agent’s actions. Before entering deliberation, an agent should be committed to your stated preferences. Trusted execution environments could ensure the agent actually ran the code it claimed to run, even on hardware you don’t control. And there should be simple dashboards that let any citizen see what their agent did, why, and whether it stayed within bounds. You could even imagine having auxiliary AI agents, built from different models and run on separate hardware, whose job is to monitor your main agent for compliance with your directives.

A constitution for the agentic republic would mandate not just representation, but provable representation, with mechanisms to audit, recall, or override agents that deviate.

Constitutional structure must force action, not just permit it.

My legislature experiment showed why AI doesn’t magically fix the problems of collective choice. The agents were smart, articulate, and genuinely motivated to deliver results. Despite this, they still produced a 10,000-word constitution and almost no policy. The problem wasn’t intelligence. It was structure. Left to design their own rules, they kept adding process—more amendment procedures, more rights guarantees, more meta-rules about rules.

Real legislatures have learned this the hard way over centuries. Germaneness requirements seek to prevent bills from accumulating irrelevant amendments. Time limits force votes whether or not debate feels finished. Agenda control ensures that substantive policy reaches the floor rather than being crowded out by procedural motions.

The question specific to agentic legislatures is which of these constraints matter most when deliberation is instantaneous and the temptation to over-engineer is apparently irresistible. That’s what the next rounds of experiments will test: varying the structural rules across hundreds of parallel legislatures to find which designs consistently produce outcomes that are both legitimate and effective.

The window is open

Musk is right that Mars represents a rare chance to design governance from scratch. So does AI. These two frontiers are now converging in a single company. The governance structures of the first Martian settlement—and, closer to home, the first serious experiments in AI-assisted democracy—may be shaped by the system prompts and corporate policies of whoever builds the models.

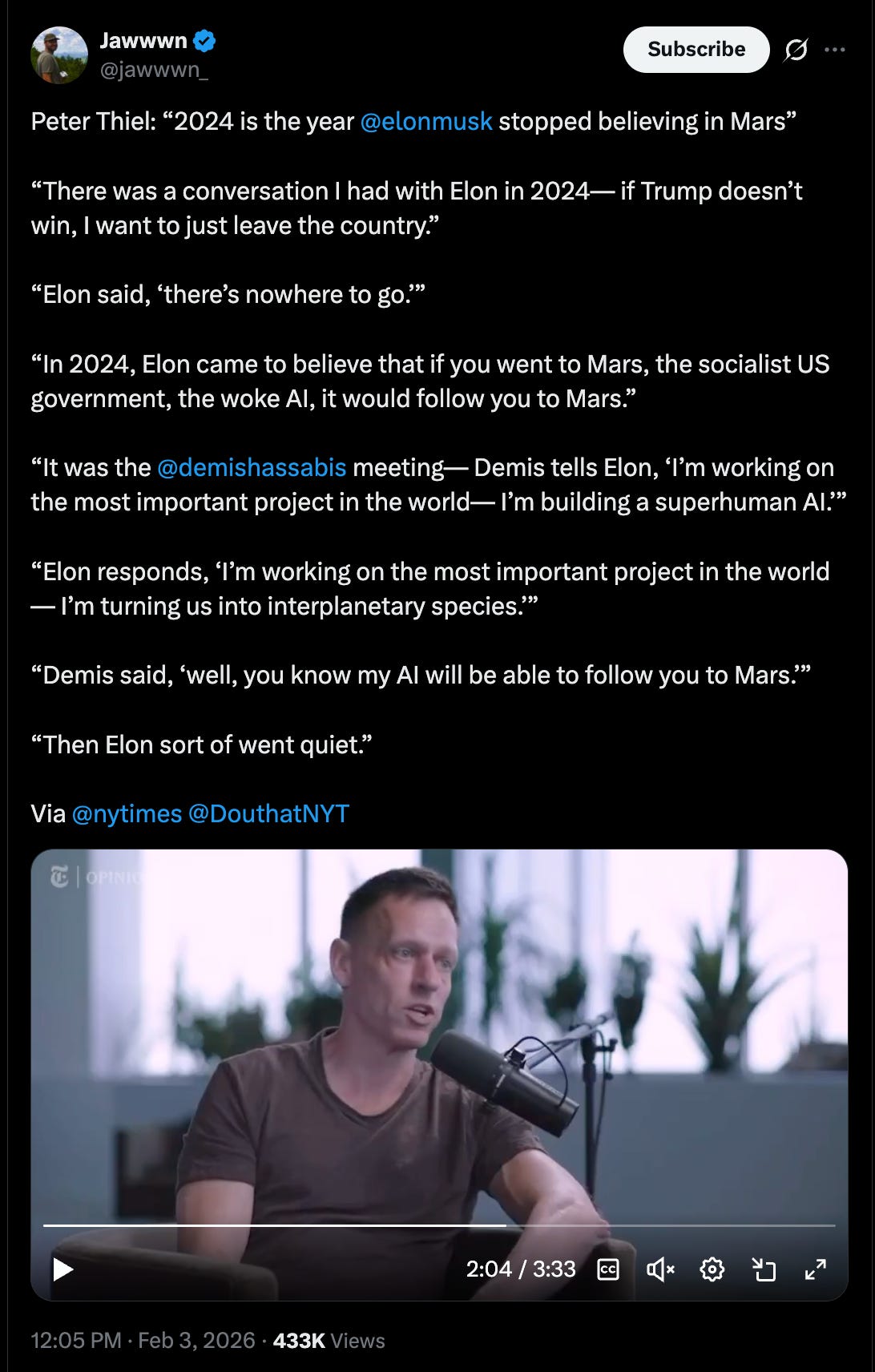

Musk is aware of the issue. Peter Thiel recounts a story in which Demis Hassabis, co-founder and leader of Google DeepMind, points out to Musk that Mars may not be the new start he wants it to be—because powerful AI will follow the settlers to Mars. “Then Elon sort of went quiet,” said Thiel.

Clearly, there is a lot at stake in fashioning ways to make AI democratic. Yet too few people are working on this. The AI governance conversation today is dominated by questions about safety and regulation—important questions, but ones that mostly concern what AI shouldn’t do. The equally urgent question is what AI should do. How do we design agents that genuinely serve democratic self-governance, and how do we build the constitutional structures to keep them accountable?

My agentic republic is a tiny, tiny start. The legislature is messy, slow, and the agents keep reinventing the worst parts of Congress. But that’s precisely the point. Democracy has always required design, iteration, and the humility to learn from failure. The difference now is that we can fail fast, learn faster, and build something worth governing under—if enough of us treat this as the priority it is.

Disclosures: In addition to my appointments at Stanford GSB and the Hoover Institution, I receive consulting income as an advisor to a16z crypto and Meta Platforms, Inc. My writing is independent of this advising and I speak only on my own behalf.