The 100x Research Institution

For the past few months, I’ve been running an experiment that felt both thrilling and vaguely unsettling: could I automate myself? And what would that mean for the future of academic research like mine?

To find out, I took a paper I published in 2020 on vote-by-mail, handed it to an AI coding assistant, and asked it to replicate the findings from scratch, then extend the analysis with new data.

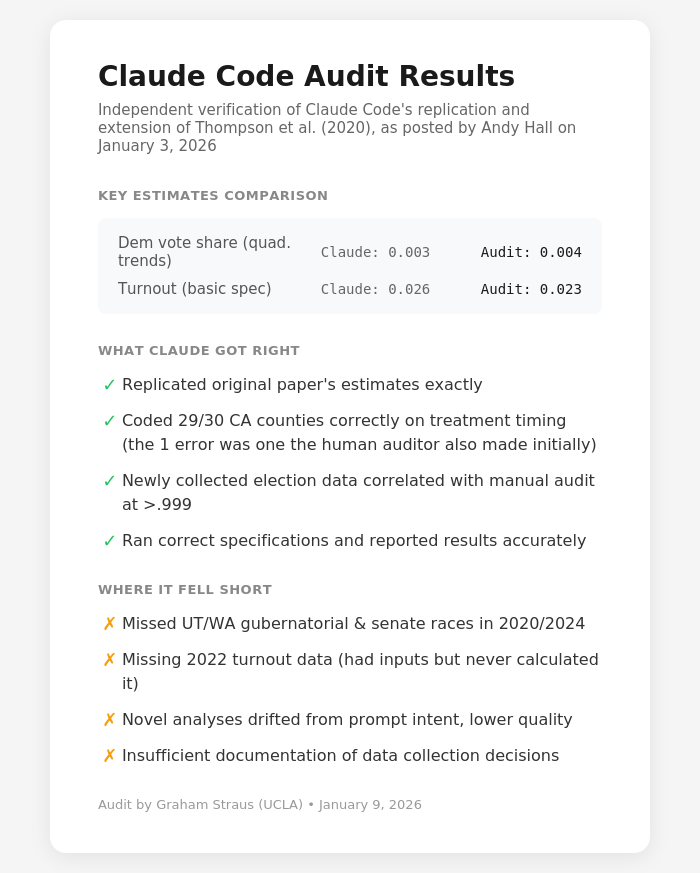

Then I did something that, as far as I know, no one else has done yet. I commissioned an independent audit of the AI-generated paper. Graham Straus, a PhD student at UCLA with no prior involvement in the project, updated the original paper “manually”—that is, without any AI assistance. He collected the new data from primary sources, cleaned and checked it, wrote new code, and developed the ground truth to compare Claude’s results against. Then he went through Claude’s code line by line, looking for mistakes big or small that might explain any discrepancies between his estimates and Claude’s.

The bottom line: Claude’s estimates were remarkably close to Graham’s.

It coded 29 of 30 California counties correctly on treatment timing.

Its collected data correlated above .999 with manually collected figures.

It made mistakes—missed some races, failed to run calculations it had the inputs for, documented poorly. But it produced, in less than one hour, work that took a trained researcher several days to verify.

The results have changed how I think about my work, my field, and the future of research institutions.

AI experiments at scale: what could 100x research look like?

Here’s a question I posed to my graduate students: What would it mean to produce research with 100 times the scope of our vote-by-mail study?

Not 100 times the length. 100 times the effort—because that’s what AI now makes plausible.

Consider what that actually means. Our original vote-by-mail paper took months of work: collecting election data, cleaning it, coding treatment timing, running specifications, iterating on robustness checks. Claude replicated and extended that work in under an hour for about ten dollars. If we could run 100 such analyses in parallel—or one analysis 100 times deeper—what becomes possible?

The obvious answers are useful but not super exciting. More robustness checks, larger meta-analyses, deeper empirical exercises. These are valuable but constrained by something AI cannot change: the supply of usable variation in the world. No amount of computational power can manufacture new natural experiments.

The more consequential opportunity lies elsewhere, I suspect: research that was previously impossible to even attempt.

Living research that never goes stale

Here’s what struck me most about extending my own paper: I could do it again, automatically, after the next election cycle. And after every election cycle from now on.

Academic research currently works like this: you spend two years on a paper, publish it, and the findings become frozen in time. By the time anyone reads it, the world has usually moved on. What if instead the most important empirical findings in political science were maintained infrastructure—continuously updated, publicly available, responding to new data as it arrives?

Imagine the vote-by-mail study as a living dashboard. Every time a state changes its mail voting rules and holds an election, the system detects it, pulls new data, re-runs the analysis, and updates the estimates. Policymakers debating election reform in 2028 wouldn’t cite a paper from 2020—they’d check the current state of knowledge, updated through the 2026 midterms.

This isn’t speculative. I’ve already done the first iteration. The infrastructure to make this continuous is well within reach.

Here are a few specific examples of living research that could transform how we understand politics:

Real-time ideology estimates for every federal and state candidate, updated daily as campaign finance filings and public statements arrive. Track pivots as they happen in tandem with the media, and correlate candidate positions with electoral outcomes.

A continuously updated tracker of AI model political bias, running independent, standardized ideological tests on every major model after each fine-tuning update—creating crucial accountability infrastructure that doesn’t currently exist.

Analysis of every bill proposed in all 50 state legislatures, updated daily. Identify model legislation. Track which ideas spread across states and why. See the patterns no human could spot, and gain a deeper understanding of political trends.

Make the replication crisis structurally impossible through automated verification

Here’s a simple idea that becomes obvious once you’ve seen Claude replicate a paper: every new empirical paper should ship with proof that an AI agent successfully reproduced its results from the raw data.

No “replication files available upon request.” Not code posted to a repository that no one will ever run. Actual verified replication, performed automatically before the paper is even posted.

This was impossible when replication required a trained researcher spending days or weeks checking someone else’s work. But Claude is happy to do it!

If we take this seriously, we could make non-replicable research structurally impossible to publish.

Synthesis at scale

We already knew AI was good at ingesting text. But with AI agents, we can deploy them to collect the data too—unlocking research on massive, highly complex political processes that no team of humans could easily tackle. Here are two example ideas to give you a sense.

Reconstruct the complete legislative history of the U.S. tax code. Analyze every debate, committee report, and markup. Trace each provision to its origin. Understand how the code became what it is. This project would have required dozens of researchers working for years. Now one person could direct a swarm of agents to do it.

Build a complete database of electoral rules across every democracy. Analyze every electoral law, constitutional amendment, and reform debate across 100+ democracies. Track how rules change and why. Create the foundation for truly comparative research on democratic institutions. (This idea was suggested to me by Lucia Motolinia.)

These aren’t incremental improvements to existing research programs. They’re entirely new categories of scholarly work.

Build and deploy real systems

Finally—and this is perhaps the most radical departure from traditional social science—AI lets us build functional prototypes of new tools and test them in the wild much faster and more easily than before. Indeed, just this week, Claude released a new tool called Claude Cowork that they built in less than two weeks, all in Claude Code! We would be crazy not to bring these tools into how we do academic research immediately.

We can use this powerful new ability to design, roll-out, test, and iterate on all kinds of new tools for politics that have never been tried before. Here are a few random ideas I’ve come up with this week:

A communication and deliberation platform for school-district parents designed to surface quiet pragmatists instead of amplifying the loudest voices. Actually deploy it. Collect data on what works.

Software to help legislators synthesize complex policy issues, pulling from diverse sources to create analysis tools. Partner with legislative staff to test it.

AI forecasting agents benchmarked against prediction markets, generating probability estimates for political events and learning systematically from their failures.

New governance mechanisms prototyped in DAOs. Democracies can’t experiment with voting rules—the stakes are too high. But blockchain organizations can. Encode different electoral systems as smart contracts. Deploy in real organizations making real decisions. Generate evidence that was previously impossible to obtain.

Across all these, there’s a common thread: AI doesn’t just let us do the same kinds of papers we were already doing. It lets us do things we couldn’t have attempted before.

A New Kind of Automated, Verifiable Research Institution

If we harness it correctly, AI creates opportunities to explore a fundamentally different way to organize how we produce knowledge about the world.

Picture this: A research institute where a handful of senior scholars each direct dozens—eventually hundreds—of AI agents on ambitious, coordinated research programs. Not a traditional lab with lots of graduate students, postdocs, and administrators. A small team of experts who provide the questions, the judgment, the interpretation, while agents handle data collection, analysis, robustness checks, and literature synthesis in parallel.

One person might be able to run a research program producing replicable, systematic, and continuously updated research on a major area of interest—whether it’s AI and politics, modernizing the government, the science of election administration, etc.---that currently requires a team of five or ten.

A research swarm prototype

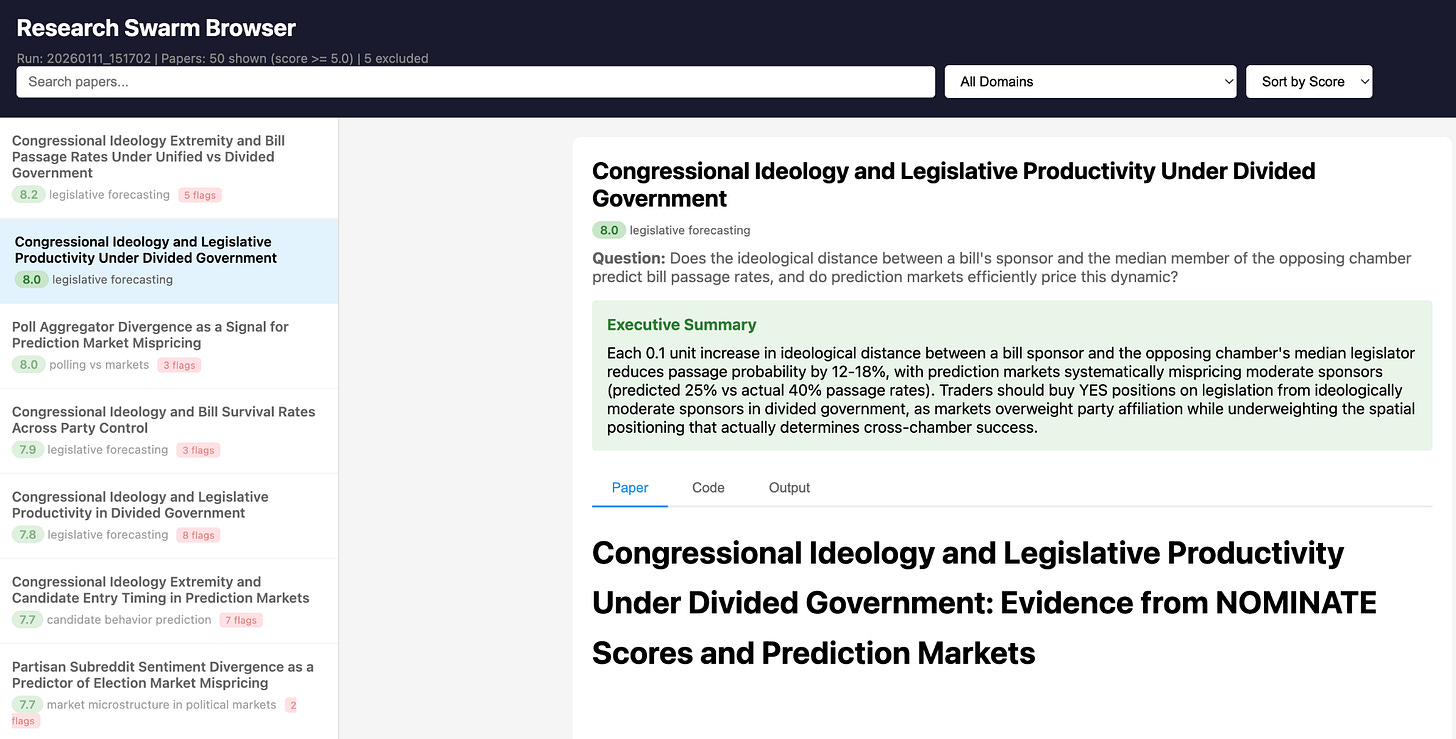

To envision how this might work, I built a prototype. Based on a repository of published social science research from across the discipline, an army of AI agents proposes new potential research ideas. I then use my LLM council design to evaluate the ideas and pick out the most promising. The AI executes each of these studies, and then another LLM reads and grades them.

All of the results go into my “research swarm browser” where I can see all of the papers, their summaries, the AI grader’s evaluation and comments, and all of the underlying code and output. It’s obviously early days for this prototype right now, but the promise is clear: instead of building out a single idea at a time, expert researchers can consider whole constellations of questions, apply their judgment, and press forward with the best ones.

To be clear, “best” does not and cannot mean which ones are statistically significant—and the browser can be designed to obscure this information, or to adjust for multiple testing—rather, it means the most insightful and the most promising to pursue more deeply.

This is what it looks like with almost no capital deployed; I use cheap models throughout. The ideas and evaluations will improve massively if I use frontier models. It’s amazing to think what such a system might come up with if I 10xed or 100xed the inputs—asking frontier models to do the thinking, to engage in debates, and to iterate on all the best ideas.

The economics demand it

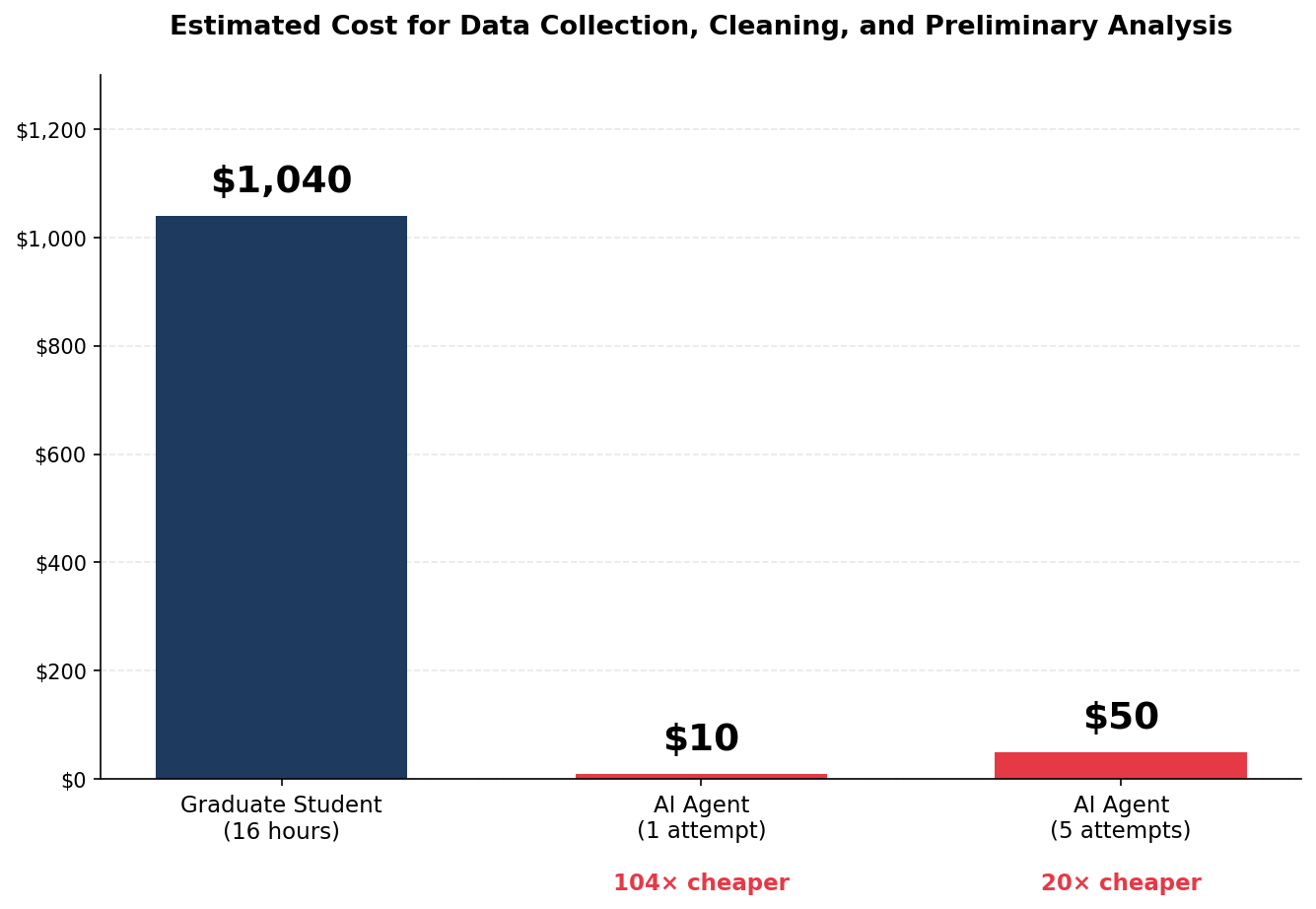

A frontier AI model running a heavy day of empirical social science research right now costs well under 100 dollars a day for many of the types of research problems I work on. Here’s the math. Anthropic prices Claude Opus 4.5, its most capable model, at $5 per million input tokens and $25 per million output tokens. A heavy day of AI-assisted research for me—running code, analyzing data, drafting prose, iterating on errors—might consume about 1 million input tokens and 200,000 output tokens. That works out to $5 for input plus $5 for output: roughly $10 for a full day of intensive work. Lighter days cost less. And while the marginal cost of asking an AI to try one more robustness check or rewrite an analysis isn’t literally zero, in practice it’s often just a few cents.

Based on my own experience with research—and on watching Graham’s experience last week—a very skilled graduate student would likely need two full days of work to complete the vote-by-mail extension (and one with less experience in the domain might take weeks). At $65 per hour, which is a plausible estimate for the all-in cost, a graduate student spending two workdays cleaning data and running preliminary analyses would cost about $1,040. Based on my estimated token usage for the same vote-by-mail extension, an AI agent can attempt the task for about $10—and if it fails, you can simply run it again with a different approach for another $10.

Clearly, the economics of organizing research have changed. Sufficiently expert grad students should be deployed for more sophisticated tasks while AI handles the more menial but still essential ones. Meanwhile, everything is replicated and audited on the fly before it’s ever released to the public.

What it would take to build

The requirements to test out this new research institute are almost comically simple:

Compute funding for researchers. Buy API credits for Claude and other frontier models and give them to researchers. At my current rate, I’m on pace to spend less than $5,000 on API credits this entire year. Which is insane. And it’s mind-boggling to consider the kind of research I might be able to produce if I scaled that by 10x or 100x.

A commitment to hire ambitious researchers and get out of their way. No administrative bloat. No committees. No multi-year grant cycles. Hire people with important questions and the judgment to pursue them, give them AI credits, and let them cook.

That’s it. Two ingredients.

This ultra-lean new institution could also train researchers differently from the start. If AI handles more mechanical work, the valuable skills shift: research design, theoretical intuition, knowing what questions matter, interpreting results, communicating findings. Hands-on data work becomes less central. Not zero, because you need to understand it to oversee it, but not the core of training. The graduates would be native to the new paradigm—and they’d become the leaders of the next era of social science.

Partnerships between frontier labs and empirical researchers

Individual researchers can make progress on their own, and there are ways of working that researchers can begin implementing now that I’ll be sharing soon.

But some opportunities require collective action—and represent openings for donors, foundations, and frontier labs to accelerate the transformation.

The current AI models are trained on general reasoning, code, and math. But empirical social science has its own failure modes, and the audit of my vote-by-mail paper showed them clearly: the model missed races, had data it didn’t use, drifted on novel analyses, and provided poor documentation.

Frontier labs should care about this. Academic researchers have produced thousands of papers with replication files—each one a ground truth that could be used for training. You could train models to run that code and verify their own outputs. You could build reward signals based on replication success and penalties for drift, which happens when analyses depart from the stated question without flagging it.

The partnership model is straightforward: labs fund researchers embedded in universities to develop and test AI-assisted research workflows, with findings shared publicly. Labs bring researchers into their teams to work directly with engineers—the researcher brings knowledge of how analysis goes wrong, the lab brings the capability to fix it. Labs fund students working on AI-research integration, creating a generation trained in both domains.

There’s also a deeper technical requirement: for AI-assisted replication to work at scale, we eventually need systems that produce the same outputs given the same inputs, as Sreeram Kannan pointed out to me. Verifiable, deterministic AI—where you can confirm that a claimed output actually came from a specific model running specific code. Without this, we can’t actually fully replicate AI-powered studies because the AI is non-deterministic. Each time you run it you could get a different answer. This is a hard problem, but it’s one frontier labs and blockchain experts may be positioned to solve together.

The risks if we get this wrong

I’m genuinely excited about this future. But I also see real dangers.

Proliferating slop

If the barrier to producing empirical work drops dramatically, much of what gets produced will be wrong. The audit showed AI drifting on novel analyses, missing obvious calculations, documenting poorly. Scale that up without quality control and you get a flood of confident-sounding garbage that will overwhelm our journals and our attention while making us less informed.

Encouraging unimportant but verifiable research

AI verification and extension works best on small, well-defined empirical tasks. If that’s what gets rewarded—because it’s what AI can check—we might see even stronger pressure toward incremental work. The ambitious, creative, theoretically risky research that moves fields forward could get crowded out by the easily verifiable.

Making p-hacking worse

As my research-swarm prototype suggested, these tools could be used by researchers to search over the space of many possible analyses and just report the “statistically significant” ones—p-hacking on steroids. If our standards of evidence don’t change, this is something that obviously will happen.

But we can mitigate all three of these problems if we build the right institutions. These institutions need to elevate expert researchers who can oversee AI, audit its outputs, and stay in touch with a wide variety of practitioners and everyday people to keep track of what questions we deem worthy of study. And they need to expect much stronger forms of evidence—from larger datasets repeatedly evaluated over time as new data arrives—to avoid p-hacking.

This way, we can drive towards replicable research on the world’s most important questions, rather than generate meaningless slop or highly accurate, super marginal contributions.

Conclusion

I started this experiment wondering if I could automate myself. The answer is: not yet, and maybe not ever in the ways that matter most.

But I can automate enough to change what’s possible. Data collection that used to take weeks now takes hours. Robustness checks I would have skipped for lack of time now run automatically. Replications that didn’t make sense for most people to dive in on now cost ten dollars and take less than an hour.

The question now is what we do with that freed-up capacity. And whether we can build institutions that channel it toward research that actually matters—research that’s more rigorous, more ambitious, and more relevant to the problems Americans face.

With the capabilities of the underlying models rapidly quickening, there’s a major opportunity for academia to respond. What if research became a much more effective critical infrastructure—continuously updated, publicly available, responding to questions as they arise? Can we build research institutions that operate at internet speed? Could this help elevate the importance of academia in the political sphere?

The technology is nearly ready. The question is whether we have the will to build the institutions it requires.

I think we do. But it won’t happen by itself.

Disclosures: I receive consulting income from a16z crypto and Meta Platforms, Inc.

Really interesting point that if AI handles more “mechanical work,” the scarce skills shift toward design, judgment, and interpretation.

How do you think graduate training should adapt to that? In particular, what “manual” skills do you still think students need to practice themselves (even if AI can do them faster) because they’re essential for developing good judgment?

Interesting things to consider re future of education: